April 27, 2014

Thursday last week, I saw my first bobolinks of the season, in the marshes of the Tomoka River near Tomoka State Park. Several flocks of 30-40 birds were winging across the marsh, with occasional dink notes. It was the calls that first made me aware of them. I saw more bobolinks on Saturday – a flock of perhaps 100 birds or so flying over the marshes and impoundments of Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area.

Bobolinks are probably my most anticipated spring migrant, at least among the species that I see reliably every year. When I read the listserve reports of amazing warbler lists being tallied at Ft. DeSoto and some of the Brevard County sites, I suffer from severe attacks of envy, and in those moments have dozens of new most-anticipated species. But I have yet to see a Swainson’s warbler, after decades of birding, so snagging that one doesn’t appear to be imminent. But I do see bobolinks somewhere every year, and that almost makes up for the more glamorous stuff I can’t make myself drive hundreds of miles to see.

But bobolinks count for a lot. It’s a pity we get to see them for such a short time each year; they are very interesting little blackbirds. Bobolinks are devoted seed-eaters; the epithet in their latin name Dolichonyx oryzivorus explicitly references their fondness for grain crops (oryzivorus = rice eater). The color pattern of males in breeding plumage is splendid and rare, one of the relatively few species of birds to exhibit reverse countershading, in which the upper surface is more brightly colored than the underside. The more typical countershading places the darker hues on top and lighter below, which is hypothesized to make them less apparent in a top-lit environment. Reverse countershading does the opposite – it makes the bird stand out against its background. Not surprisingly, bobolinks show a high degree of sexual dichromatism – the females are predominantly a lovely straw-colored yellow-brown, and so are the males during the non-breeding season. The highly apparent colors of the male are coming in while bobolinks are in Florida – some males still show signs of molt going on.

The reverse countershading of a male bobolink in alternate plumage makes them very conspicuous in open environments, like the grasslands where they breed.

Their extreme sexual dichromatism may be related to their breeding system, another unusual component of their life history. The majority of passerines are monogamous, but bobolinks are one of a number of blackbird species that practice polygyny, at least occasionally. Some males have multiple mates, usually 2 but ranging up to 4. The quality of a male’s territory is probably a big factor determining which males get multiple mates while others are monogamous, but you have to figure the visual displays of the male play some part. Quite likely, the two traits are correlated – males with brighter plumage probably also have better territories and other qualities of interest to a discriminating hen bobolink.

Bobolink males arrive on their breeding grounds before females to stake out the best territories, and maybe get a second mate.

What I love most about bobolinks though is their exuberance for life. They seem to almost always be on the move, with definite places to go to in mind. Most of my sightings of bobolinks are of flocks in transit, and my views of them are cruelly brief. But every now and then I get to see a group working methodically through an overgrown field or marsh, birds in the rear of the group constantly leap-frogging those near the front. And if I’m really lucky, I get to hear a big flock in which the males are singing. The song of the bobolink is one of the most rollicking, joy-filled vocalizations of any bird I’ve actually experienced. How’s that for egregious anthropomorphism?

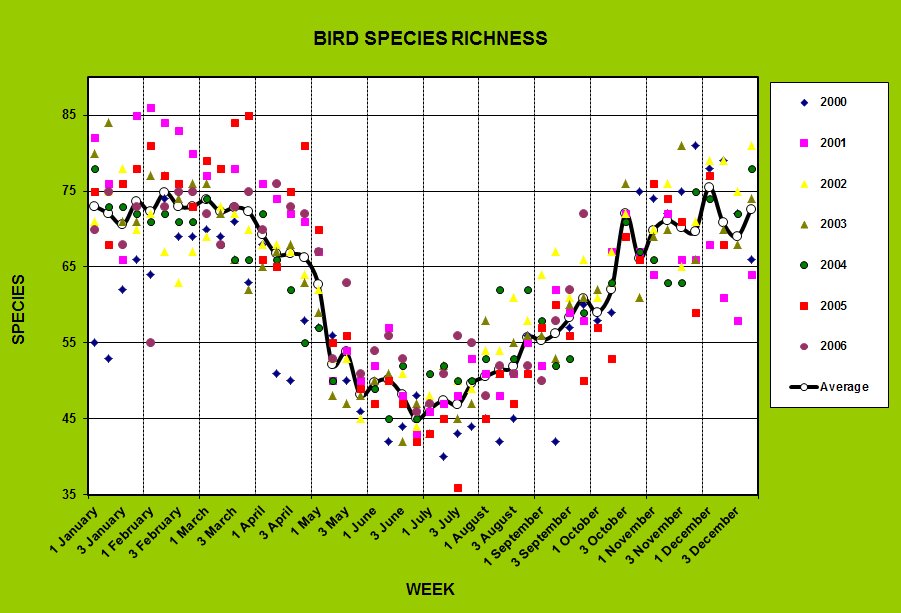

As much as I love seeing bobolinks when they finally appear in late April, they bring mixed emotions. They are the tail of the progression of migrants that has snaked through the peninsula in the previous several months. And as the last stragglers of those transient migrants finally leave Florida by the second week of May or so, an ugly and inexplicable fact hits me in the face again every year – Florida’s summer bird diversity sucks. Okay, so that’s a massive overstatement – even at its worst, Florida’ avifauna is always amazing, but it reaches its nadir of diversity in mid-summer. And preceding that low point, all through the latter half of spring, diversity and abundance of birds generally follows a protracted and depressing downward slide.

What makes this vexing to me is that it is exactly the opposite of the seasonal patterns of bird diversity for birders in most of North America. At a time when most birders are enjoying a dramatic increase in abundance and diversity, Florida birders have to wait until fall migration begins in mid-summer for avian diversity to begin to climb. Bird species richness reaches a peak in Florida in late-winter to early spring, and then crashes in late spring, in the last week of April and first week of May. The graph below shows the severity of the decline in diversity – these data were collected over the course of 7 years of surveys at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area in Lake County, and though they don’t represent the entire range of inland habitats, they are a pretty accurate representation of changes in diversity in peninsular Florida.

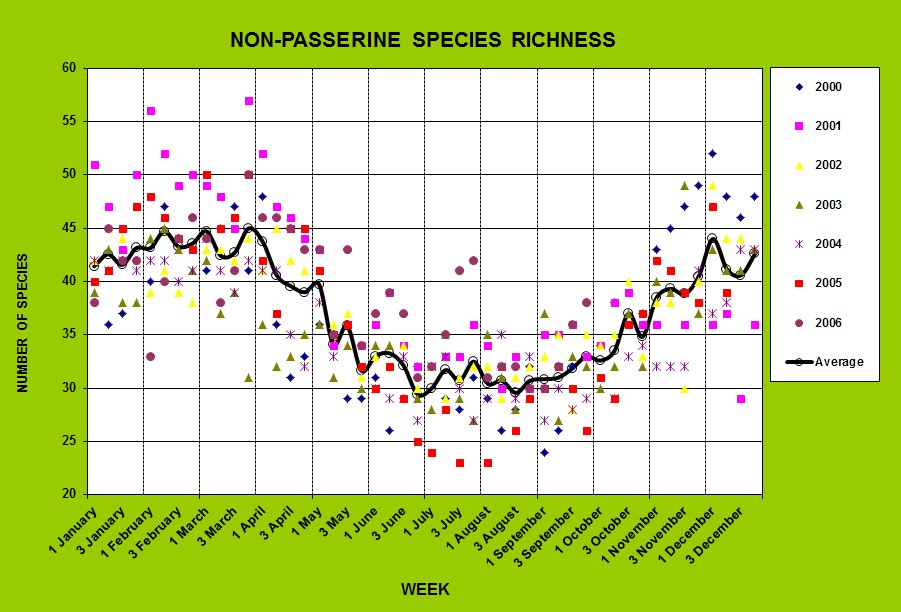

This decline in diversity isn’t limited to any one specific group of birds – it’s a general phenomenon among many taxonomic groups. The graphs below show the seasonal changes in diversity for 2 taxonomic divisions – passerines (Order Passeriformes, the perching birds) and non-passerines (all other orders), and the difference in the overall pattern between these two groups is minimal. Breeding diversity for most taxa of birds that occur in Florida is at a minimum in the summer.

The decline in diversity in spring is a bit more drastic for passerines, but in general most bird taxa show the same patterns.

Every spring after the semester ends, I drive to northern Virginia to visit my dad for a week, and spend as much time as I can in the glorious Virginia countryside when bird breeding activity is kicking into high gear. The difference between Virginia and Florida in both diversity and abundance of breeding birds is obvious and inescapable.

Part of the reason for such divergent phenological trends in diversity between Florida and the rest of eastern North America derives from the incredibly high diversity of wintering birds here, of which I’m very appreciative. But it makes the dearth of birds during the breeding season so much more painful and sad. When they leave to repopulate the north, they aren’t replaced by tropical migrants coming in to take their place. What’s really puzzling to me is why so few of the species that winter here don’t establish breeding populations. There are so many species that are abundant breeders in the mid-Atlantic for which there appears to be suitable habitat for breeding, but for whatever reason, they don’t breed here. Take the ubiquitous winter visitor, the chipping sparrow. They are common breeders in Virginia in a variety of human-modified environments, many of which seem to be replicated in Florida, yet they don’t breed here. It’s something of a conundrum to me why so few sparrows breed in Florida – the specialized Bachman’s sparrow is the only breeding sparrow found in inland habitats in most of peninsular Florida (the critically endangered Florida grasshopper sparrow has a very limited range and is an extreme habitat specialist in the dry prairies of the southern half of the peninsula). In Virginia, it’s easy to find chippers, song sparrows, grasshopper sparrows, and field sparrows in a variety of successional or disturbed habitats during the breeding season. Why are there so few breeding species of sparrows in Florida?

Indigo buntings are common as dirt in agricultural or successional habitats in northern Virginia, but far less common as breeders in Florida.

Even for species with wide breeding ranges that do breed in Florida, like blue grosbeaks or indigo buntings, the difference in abundance between Florida and Virginia is striking. In mixed agricultural habitats, indigo buntings are as regular as telephone poles along some rural roads; it’s hard to find a spot in appropriate habitat where you can’t hear one singing somewhere. In Florida, indigo buntings aren’t terribly difficult to find as breeders, but in nothing like the densities seen further north.

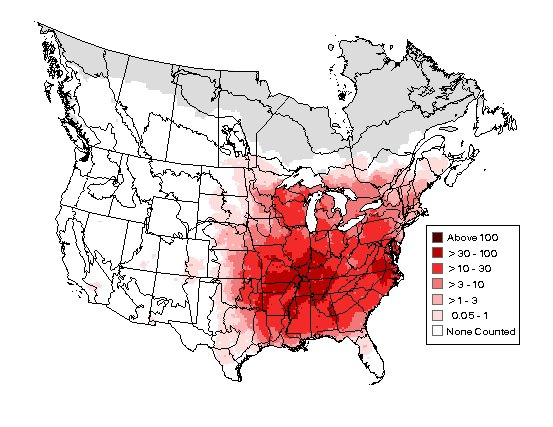

This abundance map of indigo buntings during the breeding season was prepared from Breeding Bird Survey data by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The difference in abundance between most of the eastern half of the continent and Florida is huge.

For now, all I can do to deal with the loss of birds that’s underway is to learn to appreciate even more the hard-core birds that actually stay here to breed. And look forward to the first southward movement of migrating passerines, which will begin some time in July. That’s not that far away.

This is so interesting and beautiful — I love your writing and photos!

Very interesting article and some great photography.

Thanks, Jean and Bob.

I wish I could answer your question about the few number of species of sparrow breeding in Florida, Pete. My guess would be that they are here, but in such few numbers that we are unaware of their presence (for the time being). Obrock very recently advised me that Bobolinks are running late at Harns Marsh Preserve in Lee County. In my first and mere hour of observation of the species in 2013, I can corroborate the very interesting leapfrog behavior of the birds.

Lovely read + lots learned. Good stuff lovingly and learnedly penned. You sir are a quill-master.

A quill-master, David? I consider that the highest praise, especially coming from you. Many thanks.

Thanks for your thoughts, Bob. I don’t really think there are cryptic populations of breeding sparrows in peninsular Florida – if you look at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s abundance maps (http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/ra2012/ra2012_red_v1.html ) for the sparrows I mentioned, and lots of other breeding passerines of the eastern US, you’ll see the same pattern as in the indigo bunting graphic. Declining abundance from the mid-Atlantic to the south, with many of them not breeding at all in FL or only at very low densities, sometimes restricted to just the panhandle or northeast part of the state. There’s something about the Florida peninsula that many of these birds simply find intolerable for breeding.

as always a very interesting article…I especially liked the photograph of the iall-n-a-row quintet of boblinks

Peter, I can’t believe it took me a year to come upon this site. How wonderful it is. Thanks for sharing these photos and ruminations.

Thanks for looking and reading, Tony. Come back soon.

You are right, Harry, in your observation. However, since the frrmeas out west eliminated most of the tallgrass prarie habitat, bobolinks ventured and filled grasslands opening up further east (cowbirds followed!). Bobolinks are now spread thin over a wider area and the only way to save them is through concerted efforts by all concerned. Down here, in Vermont, we are also eliciting support from private landowners who depend less on income from the land.

Thanks for your insight, Prafful. But who’s Harry?

This is so true! I become downright depressed when they leave because I know that I will not have the migraters! Right now the goldfinches are in my yard in abundance, the robins just left, the pine warblers and yellow rumped warblers are here. It is so exciting! Looking forward to the bobolinks.