December 30, 2016

It was late in December, the sky turned to snow

All round the day was going down slow

Night like a river beginning to flow

I felt the beat of my mind go

Drifting into thrush passages

Years go falling in the fading light

Thrush passages

– Al Stewart

If you’re reading this, Al Stewart, please forgive the liberties I’ve taken with your lovely lyrics. This song popped into my head sometime in the last month or two while reveling in the passage of the spot-breasted thrushes through the state, and it has become firmly embedded since. Now, every time I see or think about a thrush, I can’t stop myself from replaying this song in my head, even though it doesn’t really speak to my circumstances very accurately. Snow in Florida? Not likely.

During the past five months, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed of one of the finest perks academia has to offer – the sabbatical. Intended as a semester of research, reflection and rest from the typical mind-numbing responsibilities of teaching, a sabbatical leave is granted to applicants who propose scholarly work that the Professional Development Committee deems worthy. For my fourth and final sabbatical (we are eligible for one every 7 years), I hoped to spend the entire semester in the field studying bird behavior. And it was approved, praise be to the committee. University committees do on occasion accomplish worthwhile stuff.

Sunrise in the flatwoods of Tiger Bay State Forest. Being afield at sunrise at a different site each day of the week was an amazing experience.

As a result of the committee’s sage decision, I had the incredible privilege of being afield on over 60 days this semester. Some of my study sites included Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge in DeLeon Springs, Chuck Lennon Park, also in DeLeon Springs, Heart Island Conservation Area near Barberville, Lake George Conservation Area near Seville, Tiger Bay State Forest and Wildlife Management Area east of DeLand, and my favorite, Forest Road 33 in Ocala National Forest. Being in the field at sunrise nearly every day during Florida’s fall migration (which begins for songbirds in mid-July with the arrival of the first yellow and prairie warblers) provided me the opportunity to experience fall migration in a depth I could scarcely have imagined back in mid-August when I began the project.

As one of the greatest experiences of my life has come to an end, I’ve begun to reflect on some of the more notable sightings and insights I’ve gained about the comings and goings of birds during the past five months. The passage of the spot-breasted thrushes is at the top of that list.

The spot-breasted thrushes include 6 species, most in the genus Catharus, along with the wood thrush, placed by some in its own genus, Hylocichla. Wood thrushes were the only one of the six species I didn’t see this fall (maybe; distinguishing 2 of the 5 species of Catharus is nearly impossible in the field without hearing vocalizations). I don’t recall ever seeing a wood thrush in Florida, though they are fairly common (though declining) breeding birds of eastern deciduous forest in much of eastern North America. They breed sparingly in the peninsula, and are rare as migrants through the state.

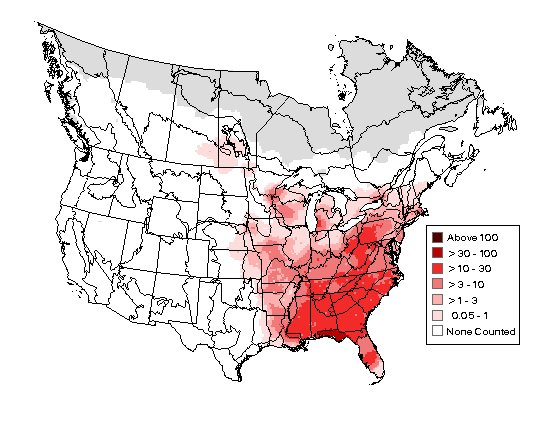

Wood thrushes are hard to find in Florida, though they are widespread breeders in eastern deciduous forest of the eastern half of the U.S.

Thrushes are birds of mystery to me. Most are primarily forest-dwellers, at least in migration, and are notable for their shy, inconspicuous ways. Furtive, fond of dense cover, and easily spooked, getting a good look at some of these birds is no mean feat. Prior to this fall, I had never seen more than two or three species during any single fall migration period.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of fall thrush migration to me is the protracted time period over which it occurs, combined with the very predictable chronological sequence of appearance of each species through Florida. All of the early migrating species leave the state to winter in the tropics, while the hermit thrush arrives last and remains in small numbers as a winter resident.

In a nutshell, the order of appearance of the Catharus thrushes during fall migration is as follows: veeries form the vanguard, arriving as early as late August, followed by Swainson’s and gray-cheeked/Bicknell’s thrushes in mid-fall, peaking in October. These three species are followed by the caboose of the bunch, the hermit thrushes, which start appearing in force in November and stick around for the winter in small numbers.

This extended movement of Catharus thrushes through Florida raises a bit of a conundrum. All of these species are breeding birds of the far north. All breed in forested or semi-forested habitats of the northern tier of states and in Canada, and all feed largely on insects and other invertebrates during the breeding season, supplementing their diet during fall migration heavily with energy-rich fruit. So they all have a broadly similar ecology and have roughly the same migratory task – traveling from the high temperate to the tropics (or just to Florida in the case of some hermits). Yet the timing of their departure and passage through Florida is so different. I have no idea why that is so, and my time in the field with these birds this fall provided no great insight, but who cares? It’s enough just to watch them and ponder.

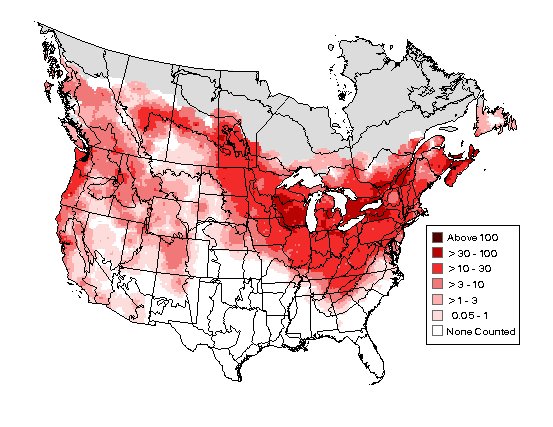

Bill Pranty’s indispensable A Birder’s Guide to Florida contains a wealth of useful data about the timing of migration of all of Florida’s birds. One of its most useful features is the information-rich bar graphs depicting seasonal occurrence and abundance of each Florida bird species. According to Pranty, veeries (Catharus fuscescens) first appear in Florida in late August and can be found as late as November, but peak in September and October, when they are rated as uncommon (found in small numbers; “sometimes, but not always, found with some effort in appropriate habitat”). They are rare before September and after October.

Veeries are one of the easier Catharus thrushes to identify. Their sparsely spotted chests and uniformly fuscous upperparts are distinctive.

I saw veeries on four days this fall, all in September. I saw my first veeries, a group of 3 birds foraging on the forest floor in mixed forest, at Heart Island Conservation Area on September 9. I saw veeries again on September 14 in the mixed cypress swamp/flatwoods of Tiger Bay State Forest (north entrance), on September 16 in mixed hammock/flatwoods of Tiger Bay (Rima Ridge tract), and for the last time on September 20, in the sand pine scrub of Ocala National Forest. Like most of these thrushes, getting a clear, unobstructed look at or photo of these shy birds is a challenge. I was fortunate to photograph them on 3 of the 4 days I saw them.

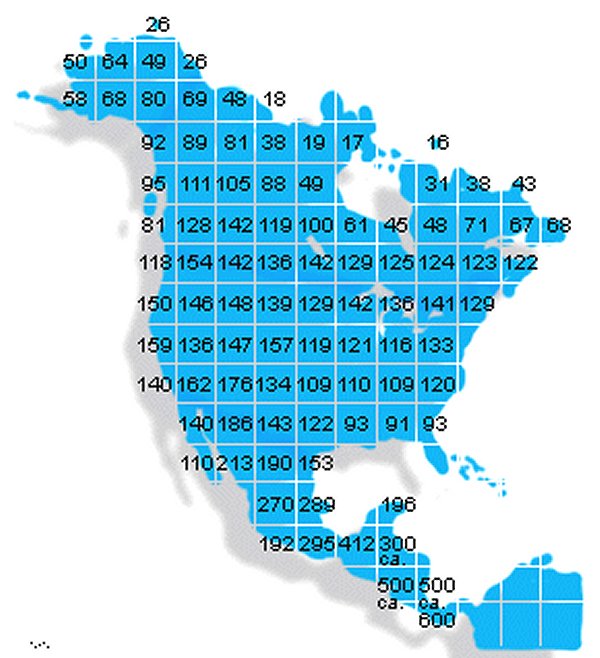

Veeries breed across most of the northern tier of states in the U.S. and in southern Canada, where they can be found in thick, wet deciduous woodlands. They are especially fond of early successional forest or disturbed areas in mature forest, and can also be found in mixed deciduous-coniferous forest.

Veery in the scrub of Ocala National Forest. Like all of the Catharus thrushes, they are quite shy and prefer to be partially obscured by cover.

The next arrival of migrant thrushes occurs mostly in October, when three species (gray-cheeked, Bicknell’s, and Swainson’s) pass through in largest numbers. Of the three, Swainson’s thrushes (Catharus ustulatus) are more easily seen. Pranty’s bar graphs show Swainson’s thrushes present in Florida from September to early December, with a peak in the latter half of September and throughout October, during which period they are rated as uncommon (rare before and after these dates).

I saw Swainson’s thrushes on only one day this fall. On October 4, they were abundant in the sand pine scrub along Forest Road 33 in Ocala National Forest. I saw at least 10 birds, and photographed 4 or 5 individuals. Swainson’s thrush is for me the most common of the early-migrating thrushes. I see them most years at least once during fall migration.

The buffy cheeks, prominent eye ring, and partial spectacle make Swainson’s thrush a pretty easy ID if you can get a good look at the head. Which isn’t always easy.

Swainson’s thrushes also have an extensive breeding range, nesting in the northeast U.S. and in some of the Rocky Mountain states, and throughout much of Canada and Alaska, where they are found in boreal coniferous forest.

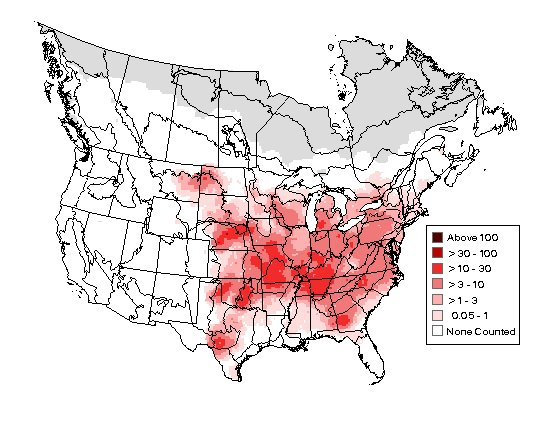

The other two species whose timing of passage roughly coincides with that of Swainson’s thrush are a puzzle. Gray-cheeked (Catharus minimus) and Bicknell’s (Catharus bicknelli) thrushes were considered conspecific (belonging to the same species) until the ‘90’s, when Bicknell’s thrush was recognized as a separate species with a very restricted breeding range. Given that these two species were considered one until only recently, it shouldn’t be a great surprise that they are VERY difficult to separate in the field based only on visible cues. They are nearly identical. Consequently, the phenology of Bicknell’s thrush migration through Florida is poorly understood, simply because there are so few confirmed sightings. Those sightings that have been confirmed suggest Bicknell’s tends to stick closer to the coastline during migration than the gray-cheeked.

Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s thrushes are nearly identical. None of the bird ID experts at the Florida Rarities FB page were able to determine which species this bird is.

Pranty’s bar graphs show that gray-cheeked thrushes pass through the state in September and October, and are considered rare throughout this period. There are only a handful of confirmed Bicknell’s thrush sightings during fall migration in Florida, so the timing of their migration is largely unknown.

My only sightings of these two species in the field were also on October 4 in the mixed scrub along FR33 in Ocala NF. Prior to this fall, I had seen gray-cheeked thrushes only once or twice in my life, and I had never seen Bicknell’s thrush. I may have seen both species this fall, but can’t be certain because of the difficulty in separating the two.

Coincidentally, my first sighting of a thrush in this species complex was on October 2, when I found a window-killed thrush in my backyard. As far as I can tell, it is a gray-cheeked thrush. Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s thrushes can apparently be identified with confidence based on specific measurements of live or dead birds in hand, but that’s beyond my skill set. That bird, which is in perfect condition, is still in my freezer. Maybe someday I’ll get a definitive ID.

This bird showed interest in the songs and vocalizations of gray-cheeked thrush, but remained deep in cover.

Tuesday, October 4, was one of the most memorable days of the fall for me. Thrush day in the scrub. In addition to the numerous Swainson’s thrushes I saw that day, I also saw a few birds that were either gray-cheeked or Bicknell’s thrushes. Especially intriguing was the observation that one of these birds responded strongly to playback of vocalizations of Bicknell’s thrush, but only mildly to those of the gray-cheeked thrush. I first saw this bird as he skulked through the dense foliage of scrubby oaks, approaching in response to playback of mobbing vocalizations, the main subject of my research. When I realized what it might be, I played territorial song of both Bicknell’s and gray-cheeked thrushes to this bird. Gray-cheeked song resulted in continued skulking. Bicknell’s song caused him to immediately pop out onto an exposed perch maybe 25’ away, where he remained for a minute or so, tail-pumping and wing-flicking.

So that had to be a Bicknell’s thrush, right? Unfortunately, no. It’s not unheard of for some thrushes to respond strongly to territorial song of other species. I’ve seen hermit thrushes become very agitated in response to veery song playback. I posted photos of the unknown thrush, along with a description of his playback response, to the Florida Rarities Facebook group, and nobody in that group of expert birders would attempt an ID. My conclusion – most likely a gray-cheeked, but perhaps a Bicknell’s.

Especially intriguing to me is that these birds respond to territorial song at all while they are on migration. None of these species sings regularly during migration, yet they will occasionally respond vigorously to song playback of conspecifics, and sometimes heterospecifics. Why? Use of playback to attract birds for observation/photography is a contentious subject, and some purists frown on the practice. Certainly it can be overused and abused, but I can’t imagine birding without using playback carefully and judiciously as a tool. The observation that these transient migrants still respond to territorial song is telling us something about the biology and behavior of these birds, even if we don’t know exactly how to interpret that observation. Such basic natural history observations are the foundation of a complete, nuanced understanding of any species. I’ve offered a defense of playback as a vital tool for birding in a previous blog.

So on October 4, I saw 4 different birds that were probably gray-cheeked thrushes, but may have included a Bicknell’s or two. What a conundrum, right? Can I place Bicknell’s thrush on my life list? In all honesty, I don’t really give a rat’s ass. I’m not and never have been a lister or twitcher. I don’t even know what my life list is numerically, though I have a pretty clear memory of which species I have and haven’t seen. I’m totally cool with calling those birds either gray-cheeked or Bicknell’s thrushes. Or both.

Gray-cheeked thrushes are the more likely of the two species to be seen in migration along most of the east coast. They have a continent-wide breeding range, extending across northern Canada and Alaska. Gray-cheeked thrushes are the most northerly of the spot-breasted thrushes in their breeding distribution; they breed in spruce-fir forest, and in alder and willow thickets on the tundra. Bicknell’s thrush has a far more restricted breeding range in southeast Canada and the northeast U.S., where they are mostly restricted to inaccessible regenerating montane forests of spruce and fir. This is a very poorly studied and understood species.

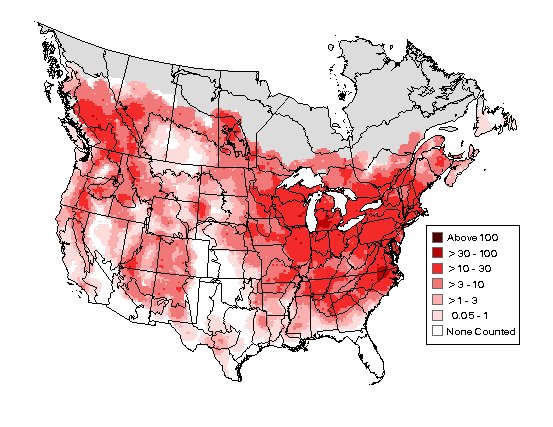

The easiest Catharus thrush to see in Florida is the hermit thrush, Catharus guttatus. This is the most abundant member of the genus in the state, and is also resident in Florida for far longer than the others. Pranty shows them as being uncommon in October, and fairly common from November through March. Unlike all the other members of its genus and the closely related wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), hermit thrushes overwinter in significant numbers in Florida. Hermits are also one of the easiest of the spot-breasted thrushes to identify; there’s not much temporal overlap between hermits and the transient thrushes, and the distinctive rufous wings and tail of hermits make ID relatively straightforward. If you can get a good look at one.

I saw my first hermit thrush of the season on November 1 in the dense riparian hammock along Deep Creek in Heart Island Conservation Area. I actually heard it first. Hermit thrushes are extremely responsive to playback of their alarm calls (churt and way calls), and will also respond to territorial song, though they don’t sing often while in Florida. They do defend fixed winter territories, though, which is an unusual behavior for wintering passerines.

I photographed this territorial hermit thrush in Ocala National Forest several times in the winter of 2015-16.

I photographed this territorial hermit thrush in November 2016, in the exact same location as the bird above. I’m pretty confident it’s the same bird that returned to overwinter on the same territory. That’s some wicked winter philopatry.

The high abundance of hermits relative to their congeners may be related to their broad breeding range, throughout Canada, the Rockies, and the northern U.S., and their catholic choice of habitat for nesting. They can be found breeding in both coniferous and deciduous forest, mixed forest, taiga in the extreme north, and in riparian woodlands in canyons of the Southwest.

Hermit thrushes have the largest breeding range of any of the Catharus thrushes, and nest in a greater variety of habitats. This one was found in a bayhead at Lake George Conservation Area.

And they are abundant. Once I saw my first, I saw hermit thrushes on the majority of my field days for the remainder of the study period. Particularly during the first couple of weeks in November it wasn’t uncommon to see a half-dozen or more hermits in a day. They became somewhat less common in December, as the pulse of migration passed and many of the migrants continued on to winter in the tropics. The abundance of hermit thrushes in winter can be stunning at times. During Christmas vacation of 2013, we found dozens of hermit thrushes in the coastal forests of South Carolina.

The spot-breasted thrush that I didn’t see this fall is one I am quite familiar with as a breeding bird in Virginia, where wood thrushes are fairly common (but declining) breeders of moist deciduous forest. This is the one spot-breasted thrush I have heard singing on their breeding grounds. The polyphonic, lush, complex, flute-like songs of wood thrushes ringing through mature oak-hickory-beech forest at dawn or dusk are emblematic of this cathedral-like habitat for me. The thrushes are the pipe organs, only far more delicious. The experience of hearing a wood thrush singing in majestic mature deciduous forest is so thrilling that I found myself imagining over and over this semester again how magical it must be to hear all of these northern thrushes singing in their pristine breeding habitats.

Wood thrushes have proven to be the most difficult thrush to photograph, for me, though they are not hard to find during the breeding season.

I don’t recall ever seeing a wood thrush in Florida, where they are actually breeders in the Panhandle. As fall migrants through the peninsula, however, they are rarely encountered. Perusal of e-bird sightings in the peninsula for the period August-November 2016 turned up less than a dozen sightings. Yet another mystery of thrush biology – why are nearly all of the northern-breeding thrushes so much more abundant in fall migration through Florida than wood thrushes? Why do wood thrushes mostly avoid migrating through the peninsula?

The other two commonly seen Florida thrushes, quite different in nearly all aspects of their biology from the Catharus and Hylocichla thrushes, are equally curious in their movement patterns. American robins are winter residents in the state, and are the last of the migrant thrushes to appear. Though they winter in huge numbers in the state, they also show quixotic behavior while here – they show a distinctly biphasic nature of habitat choice and behavior while wintering, a phenomenon I’ve written about in a previous post (Bipolar Robins).

American robins winter in huge numbers in Florida, but not until the transient thrushes have mostly completed their passage.

The other common Florida thrush is the eastern bluebird, which is dramatically different in behavior from the woodland thrushes. Not only are bluebirds denizens of open, non-forested habitats and edges, they are also permanent residents. No migratory movement at all. Like robins, young birds show spots on the breast typical of so many thrushes.

Like most thrushes, the young of eastern bluebirds show the spotted breast that is part of the adult plumage of many thrushes.

The woodland thrushes are special birds for me; seeing even one of these shy, cryptically-patterned birds elevates any birding trip to a good day. For the rarer species, like gray-cheeked thrushes, seeing them once during the migratory season is a significant event. To see secretive, uncommon birds you have to have a bit of skill, a bit of luck, and spend lots of time in the field. It’s noteworthy to me that though I spent over 60 days in the field this fall, I saw three (maybe?) of these species on only one of those days. Though all of these species are regular fall migrants through the peninsula, the vagaries of weather and frontal patterns, prevailing high-altitude winds, and other meteorological variables that impact migratory flights over and into the state all combine to make finding these birds, and in particular the rarer species, a daunting challenge. I was quite lucky this fall.

I love observing and photographing birds with such intensity that I would do what I do if there were no other rewards than the sightings, the photos, and the memories. Equally rewarding for me, though, is the window these observations provide into the workings of the natural world. Natural history is an infinitely complex subject; any one of us can only hope to scratch the surface over the course of a lifetime of study. A lifelong attention to the minutiae of natural history provides a deep understanding of the meaning of one of the great buzzwords of our time, biodiversity. Biodiversity is more than a list of species, though it is sometimes simplified to simple numeration of species numbers.

Migrant thrushes and fall foliage – a hard-to-beat combination. This is a hermit thrush in red maple (Acer rubrum).

The Catharus thrushes illustrate some of the finer points of biodiversity perfectly. Although the members of this clade are superficially relatively uniform, closer study reveals that each species is significantly different in lifestyle and behavior from the others, even though they are so similar in appearance that distinguishing some of the species from each other is nearly impossible. And this raises questions. Why do these birds, which behave similarly and feed on the same sorts of food during migration, show such distinct differences in the timing of migration and their passage through Florida? Why are veeries the first to appear, and hermit thrushes the last? What is it about the biology of hermit thrushes that allows them to winter in temperate habitats, while all of the others must return to the tropics each winter?

I’ll never answer these questions, or probably even speculate intelligently about them, but they sure are a lot of fun to think about.