September 6, 2016

I’m intrigued and mostly mystified by the cognitive processes going on in the minds of “lower” animals like snakes. Observing snakes in captivity and in the wild has at times left me with the impression that snakes aren’t the greatest thinkers on the planet; one mutt rat snake that I had for years tried on several occasions to swallow itself, beginning with its tail. It was so determined to self-ingest that I kept a wash bottle of ethanol nearby for those suicide attempts; a little squirt in the corner of his mouth was apparently distasteful enough that he would rapidly egest that part of his nether half already swallowed. Which could be as much as a quarter or more of his body length. That couldn’t have ended well. But somehow he survived the multiple auto-cannibalistic episodes.

Arboreal rat snakes, like these black rat snakes (Pantherophis allegheniensis) spend much of their days watching the comings and goings of their fellow creatures. Then go out and eat them.

On the other hand, watching the intent, patient gaze of some of my big yellow rat snakes, who would bask immobile and watch me for hours made me wonder about the amount of information these big arboreal snakes might be soaking up. Research on gray rat snakes (Pantherophis spiloides) in the southeast reveals a sophisticated learning lifestyle; they spend hours to days watching their surroundings from an aerial lair, in the process detecting and remembering the presence of rodent runs, birds’ nests, and other potential prey (Mullin and Cooper, 1998). When they are hungry, they dash out of the pad to pick up some groceries. That’s pretty amazing behavior for a snake.

What is this black racer (Coluber constrictor) thinking about? If I had to guess, I’d speculate that these guys are among the more intelligent of snakes

How do they know how to do this? It’s hard to know what’s going on in the minds (do non-human animals have minds, or just brains?) of animals from the perspective of a mechanistic understanding of cognitive processes. Neurobiologists and animal behaviorists just don’t know that much about some very basic aspects of mental functions. How and how much do animals learn? Do animals think? Can they reason and perform other logical operations? Do they have emotions and self-awareness? Do individual animals have distinct “personalities”? Do they interact with other members of their species based on what they think is going in in the other animals’ thought processes, the so-called theory of mind? These are very difficult processes to study in animals, who selfishly refuse to describe to us what is going on in their heads. Conclusions about mental processes must be inferred indirectly from specific behaviors exhibited under controlled lab conditions.

Our lack of a deep understanding of the mental capabilities of our fellow animals has one upside – it allows me to speculate foolishly and egregiously about the thought processes of snakes, which I will do below. The thought processes in question stem from my observations of one of the most audacious and single-minded behaviors I’ve ever seen by a wild snake.

Around 10 yesterday morning, I had nearly completed the 11-mile Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive. I was traveling west on Interceptor, just south of the sod fields that had been producing buff-breasted sandpipers and some other notable birds in the last few days. I had the road to myself, so I decided to do a 180 and park my car facing east on the north shoulder of the road so I could scan the flooded fields in their entirety from the driver’s side. As I turned to the right to begin the 3-point turnaround, I saw a small dark snake with rapidly twitching tail near the road’s edge on my left.

The tail twitches that alerted me to the presence of this snake were part of a larger whole-body effort to drag this frog off the road.

A snake in the road with twitching tail usually means a snake that has been recently run over, a snake in the last throes of death. I was prepared to be bummed. The unnecessary death of any snake saddens me, more so than any other kind of animal, for reasons I don’t fully understand. No bummer for me on this day, though. The little serpent, a young eastern garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), was very much alive, and intent on completing a bold and ambitious task.

A closer look at the little garter in the blonde shell-rock road revealed the pale underbelly and protruding viscera of some medium-sized frog that had been run over and flattened some time before. The little snake was a bit thin, and well under 10”. The anuran was at least 3-4 times the body weight of the snake, but that disparity didn’t seem to deter him at all. As I watched, and photographed, for the next several minutes, the little garter repeatedly tried to dislodge the frog from the road surface and drag it back to the cover of the road margin. He made no progress at all. The next plan was to try to ingest the frog in situ, beginning with a foreleg. No self-respecting, experienced garter snake would try to swallow an ungainly, long-limbed prey item like a frog by beginning anywhere other than the nose, but this little garter’s mother never taught him that trick.

The right front leg was the preferred point of attack for the little garter. Most of his efforts to swallow the frog started here.

On a couple of occasions, the little guy backed off, looked around, took a deep breath, and thought things over. And then returned to the task with renewed vigor. Ultimately he admitted defeat and slithered back into cover without his big dead frog.

What was that snake thinking during this encounter, if anything? Venturing onto the uniformly light-colored road surface was a ballsy move for a small snake that could be eaten by any of several dozen potential predators. And fast, Jack. Any of the common egrets and herons would have been on that snake like ugly on an ape; even a big passerine like a jay or thrasher would have had no problem at all dispatching that little guy.

Any of the herons or egrets would gladly scarf a little garter snake. This great blue has snagged a striped crayfish snake (Regina alleni) much larger than my little garter.

Risk-prone snakes reap the big rewards some times, but they can also pay a heavy cost. Several years ago while returning from Emeralda Marsh on County Road 42 through Lake County, I found a multiple herp fatality on the roadside. A road-killed southern toad lay alongside a DOR cottonmouth. I’m quite sure the toad died first; the cottonmouth was scavenging when it too was hit by a car. No guts, no glory.

Looked like an easy meal, but it didn’t work out that way for this cottonmouth trying to scavenge a road-killed toad.

One possibility is that the snake was behaving entirely according to a reflexive behavioral sequence genetically encoded and neurologically hard-wired. The sensory cues emanating from that dead anuran were probably intense; garter snakes and other members of the genus Thamnophis are heavily reliant on olfactory cues during prey search. For all I could tell, that dead frog was billowing huge ropy plumes of frog essence, a scent so overwhelming that the poor little snake was pulled in unwittingly and unthinkingly as if by a tractor beam.

On the other hand, what if snakes have an active mental life, and some form of information processing that might approach conscious thought processes? Was that exposed little snake frightened? Was he figuratively strutting like Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder in Stir Crazy (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNbZcT8RXgE), thinking “That’s right, I’m bad”? (Remember what I said earlier about foolish and egregious speculation?) I have to think the behavior of that particular snake was in some respects remarkable – not every young garter snake of comparable size would attempt to consume such a massive prey item. In the parlance of behavioral biology, that snake was particularly risk-prone, placing himself at increased risk of predation to get the big payoff. There are certainly other garter snakes out there that would exhibit a more risk-averse approach, and never leave the cover of the roadside. Where do these differences in behavior among individuals come from? Do they reflect genetic differences in programmed behavior, or are they the result of prior experience (learning)?

I’m going to figure this out eventually. If only that butt-ugly stinking primate in the blue car would piss off and leave me alone.

So that’s the meaningless navel-gazing section of this post. The other really fascinating thing about this observation was the behavior itself – consumption of carrion by an animal that is usually thought of as a pure predator. As it turns out, consumption of carrion by snakes isn’t all that uncommon. In a 2002 Herpetologica paper, Devault and Krochmal review the literature on scavenging by snakes, and suggest it is more widespread than previously thought, and in fact may be an integral part of the foraging strategy of some species of snakes. Scavenging is particularly frequent in snakes that rely heavily on odor to find prey (like the thamnophines) and in pit-vipers. Most pit vipers normally consume dead prey – they wait for the animal they have envenomated to die before attempting to ingest it. Often an active prey item may travel a considerable distance before expiring, with the snake eventually tracking (by odor) the envenomated prey item. Consuming carrion that they happen to encounter while tracking prey makes a lot of sense for such a predator.

In this scan from an old transparency, a pigmy rattlesnake approaches (and eventually consumed) a green tree frog that has long ago died from envenomation. It’s entirely possible that this frog was killed by a different snake than this one.

The authors found evidence for scavenging in 35 species of snakes in 5 families, dominated by the pit-vipers and fish-eating snakes, which often are heavily dependent on olfactory cues. Their review turned up scavenging by two species of Thamnophis (T. proximus, the western ribbon snake, and T. sirtalis, the eastern garter snake). Curiously, both records of scavenging by garter snakes were observations of snakes feeding on birds.

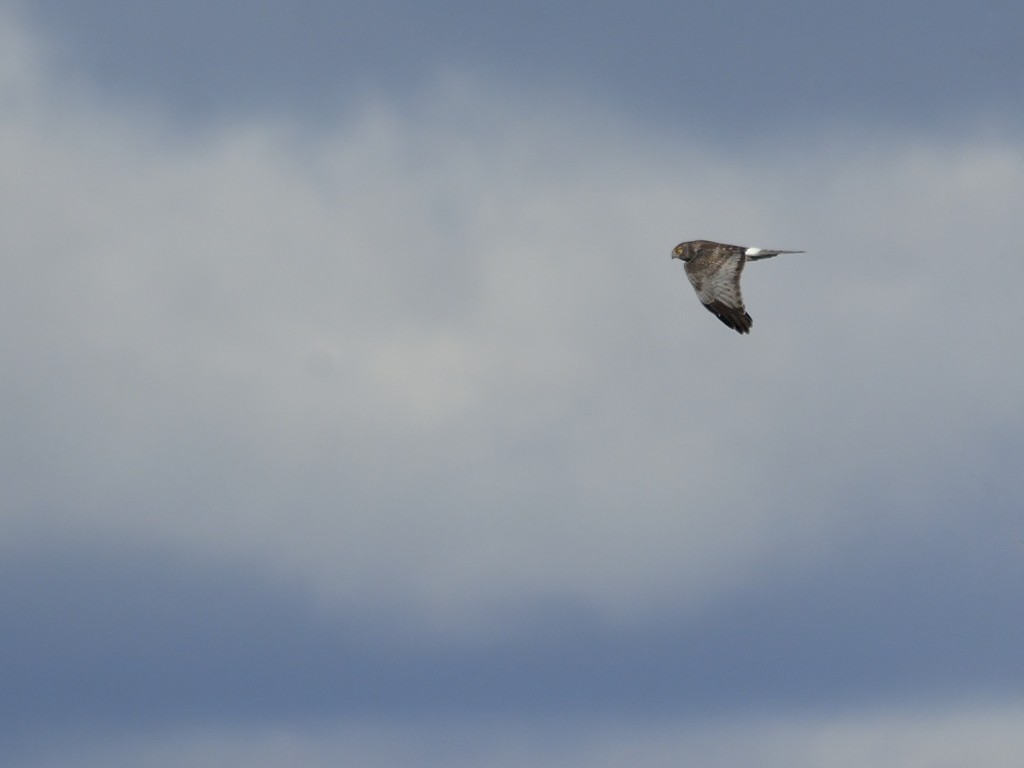

It always comes back around to birds, doesn’t it?

References

DeVault, T. L., & Krochmal, A. R. (2002). Scavenging by snakes: an examination of the literature. Herpetologica, 58(4), 429-436.

Mullin, S. J., & Cooper, R. J. (1998). The foraging ecology of the gray rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta spiloides)-visual stimuli facilitate location of arboreal prey. The American midland naturalist, 140(2), 397-401.