September 28, 2014

I’ve always been kind of partial to spiders, though at the same time just a bit intimidated by them. Although the vast majority of North American spiders are of no significant threat to people, the idea of catching a big orb-weaver in the face when I’m in the field still creeps me out if I think about it. My real introduction to spider biology at anything other than an extremely superficial level came when I first began grad school at UF, and became friends with an arachnophile, Craig Hieber. Much of what I know about Florida spiders I learned from Craig, and though I can’t say for certain that he was the one who first introduced me to the green lynx spider, I think there’s a pretty good chance he did. UF Zoology at that time was a hotbed of spider research – faculty members John Reiskind and John Anderson both did research on spiders, and mentored a number of grad students doing their master’s or doctoral research. Even H. Jane Brockmann, always one of my favorites among the faculty (“do you people say bloody over here?”), got in on the spider action, and her student Linda Fink produced some splendid papers on reproduction and defense by green lynx spiders as an outcome of her master’s thesis.

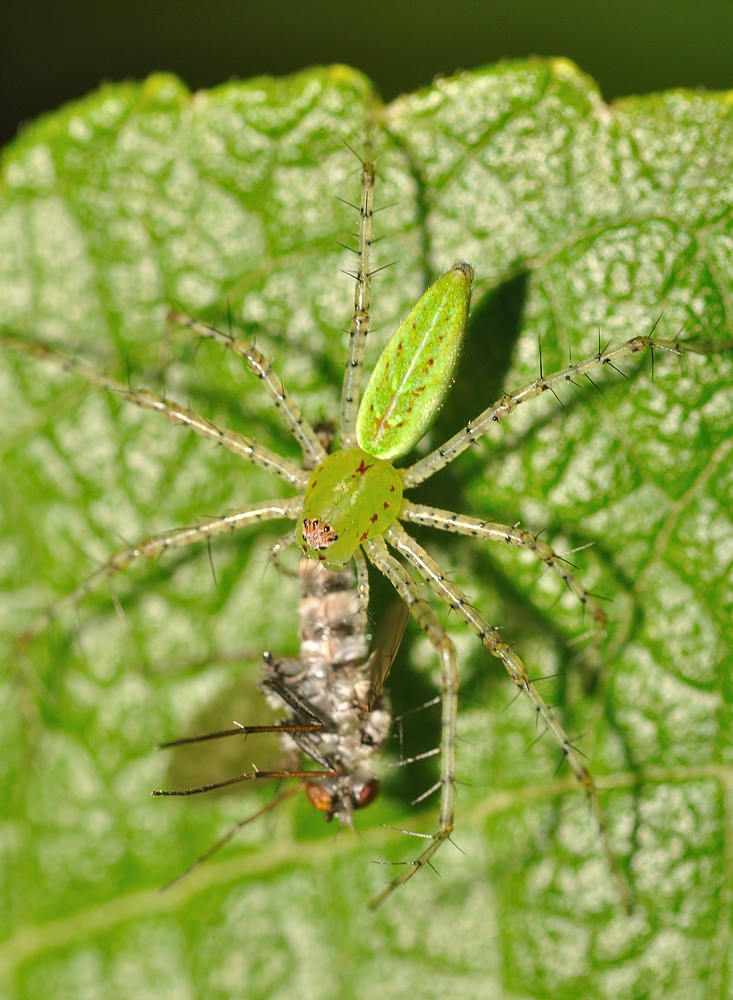

Green lynx spiders, Peucetia viridans, are one of the most common Florida spider species. They prompt the greatest number of requests for identification by the arthropod experts at the Florida State Collection of Arthropods of any spider species in Florida. Commonly found in ruderal (disturbed) habitats and edges, particularly among flowers in the late summer and fall, I’ve known about their abundance for some time. When I first moved to my current home in DeLand six years ago, the gardens I planted were loaded with lynxes. More recently, since I’ve begun spending a lot of my field time ode-cruising, I’ve been struck again how incredibly common they are. Green lynxes can be pretty cryptic as they spend large amounts of time motionless amidst an inflorescence waiting for some clueless victim to make the mistake of a lifetime, but once you’ve developed a search image, you can’t help noticing them.

They are so abundant in some habitats, including agricultural fields, that they are an effective biological control agent against some agricultural pests, particularly the many species of noctuid moths that oviposit and feed as larvae on crop plants. The good that lynxes do by reducing herbivory on crop plants is counteracted somewhat by the number of beneficial insects they consume along with the pests. Bees, wasps, butterflies and skippers, syrphids and other types of flies… the list goes on and on. Lynx spiders seem to be very opportunistic predators who will take just about any type of insect prey that they can get their fangs on.

And what lovely fangs (chelicerae) they have. Members of the family containing the lynxes, the Oxyopidae, are distinguished by their relatively tall clypeum (the portion of the “face” between the eyes and the chelicerae) and elongate chelicerae. Looking at a lynx spider head-on makes me think of an old, droopy-faced wizard. The Oxyopidae is not a huge family – a bit over 400 species in 19 genera worldwide, in Florida they are represented by only a few species in two genera (Peucetia and Oxyopes). I’ve never seen any of the Oxyopes species, but I’ve seen more lynxes than you can shake a snake hook at. They are ubiquitous at this time of year.

The high clypeum, big chelicerae, spiny legs, and unusual eye arrangement are all characteristic of the Oxyopids.

Finding them isn’t hard. I’ve seen them referred to in one source as “Inflorescence spiders”, and that is spot on. If you want to find lynxes, look for them on the inflorescences of a variety of weedy plants, including many composites. Because they are so cryptic, it helps to look for particular irregularities in flower clusters, like an out-of-place green lump in the midst of the flowers, or the translucent spiny legs projecting out from the flowers. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve found lynx spiders lurking in the background when doing post-processing of photos of other flower visitors. With their delicate green cephalothorax and abdomen, decorated by whitish chevrons in the larger females, and their nearly transparent multicolored spiny legs, there is nothing to confuse a lynx spider with.

Though I’ve been seeing and appreciating lynxes for years, I was thrilled to recently photograph a male lynx for the first time. Males are slightly smaller than females, but as in most spiders, males are distinguishable from females by their modified pedipalps. Pedipalps, or palps for short, are the pair of short leg-like appendages extending from the head, with which spiders manipulate prey or other objects. Palps are also intimately involved in mating behavior – they are the surrogate penises for males. Prior to mating, male spiders spin a pad of silk and deposit semen on it and transfer the sperm to receptacles at the end of their palps. Male spider palps are typically enlarged at the end, sometimes with syringe-like structures and extensions that aid in the process of inseminating the female. I wonder if female spiders reluctant to mate sometimes give “palp jobs” to persistent males to cool them down?

A male lynx spider, showing the enlarged palps with hook-like extension. You can click on this image (and most images on the blog) to see more detail in the palps.

Lynx spiders obtain their name from their hunting behavior. They are ambushers and stalkers, using their acute vision to track and pounce on unwary prey. I’ve never been lucky enough to see one making a kill, but I have on several occasions watched a hunting lynx make a quick dart towards pollinators approaching the flower they are sitting on. Just yesterday I photographed one that had just seconds previously captured a small darkly-colored grass skipper; the lynx had her fangs embedded in the skipper, and it slowly unfurled and then recoiled it’s proboscis as the venom took hold. At one point the struggling skipper forced the lynx to release her hold on the plant, and the spider and her skipper prey dangled from a few silk lines, spinning in the faint breeze until she regained her purchase.

Did someone say badass? Lynx spiders seemingly know no fear. They’ll take just about any prey they can inject their venom into, including some insects as large or larger than the spider. Occasionally, however, the tables are turned and insects that could be taken as prey take the spider. Many species of solitary wasps provision their nests with paralyzed spiders to feed their developing offspring, and lynx spiders are among the victims.

On a number of occasions, I’ve seen lynx spiders with prey being victimized by another arthropod colleague, though not with such drastic results as their interactions with spider wasps. Lynx prey items are sometimes attacked by hemolymph-sucking ceratopogonid flies (midges) as the spider is sucking out the liquefied prey contents. I don’t know whether the midges also attack the lynx, but they do parasitize other adult arthropods, such as dragonflies.

This leaf-footed bug (Leptoglossus phyllopus) being eaten by the spider is also hosting a big crowd of ceratopogonid flies sucking on the hemolymph.

Aside from their general ferociousness and take-no-prisoners attitude, lynx spiders show a gentle side. They are excellent mothers. Linda Fink’s research while at the University of Florida revealed that females guard their egg cases (cocoons) for several weeks after they lay the eggs, and that this defensive behavior significantly increases survivorship of cocoons when compared to experimentally manipulated cocoons from which the female had been removed. Ants seem to be the biggest threat; the female lynx will directly attack the ants, though on occasion they will chomp down on a leg and not release their grip even after death. Linda observed lynx spiders in some instances sacrificing a leg (autotomy) to rid themselves of the dead hanger-on. Their maternal devotion doesn’t protect the eggs from one other threat, though – parasitic mantidflies (Mantispidae) that lay their eggs in the spiders’ cocoons were equally common in both Linda’s control (mother remained) and experimental (mother removed) treatments.

Linda even documented a new defensive behavior for lynxes while doing her research on maternal care – they spit venom in the direction of their enemy. Although there is an entire family of spiders that specializes on spitting their gooey silk-containing venom cocktail on their prey to immobilize them (the Scytodidae), green lynx spiders are the only oxyopids known to defend themselves in this way.

If the standard defensive measures don’t work, lynx mothers will relocate their cocoon to another plant. But they do so in a unique way; they don’t carry the cocoon to its new site, as some other spiders do, but instead reengineer its attachment. They establish new suspensory silk lines anchoring the cocoon to the foliage of a nearby plant, and then cut the silk lines attaching it to its current host. The cocoon swings over to its new site and the female then secures it with more silk.

She stays with the developing eggs in the cocoon for several weeks until they hatch, sometimes refraining from feeding and starving herself in the process. The cocoon can contain 25-600 eggs, averaging about 200. Whether the female refrains from feeding or not, she will die sometime during the fall, and her early-instar offspring will overwinter, maturing and reproducing themselves about 300 days later.

My next photographic goal – obtain a cocoon or two, with attending female, and keep them in captivity until the little dudes hatch. Is there anything more adorable than a batch of a couple hundred little lynx spiderlings being doted on by a loving mother? I doubt it.

References

Fink, L.S. 1986. Costs and benefits of maternal behaviour in the green lynx spider (Oxyopidae, Peucetia viridans). Animal Behaviour 34(4): 1051-1060.

Fink, L.S. 1987. Green Lynx Spider Egg Sacs: Sources of Mortality and the Function of Female Guarding (Araneae, Oxyopidae). Journal of Arachnology 15(2): 231-239.