Setember 20, 2013

Fall migration, for many of the bird-obsessed like myself, is the best time of year to be in the field. Spring may bring males in peak breeding plumage and song, but the sheer numbers of birds make fall migration more spectacular for me. Especially given the eccentricities of Florida’s seasonal variation in bird diversity (low breeding diversity, high wintering passerine abundance and diversity, highly variable numbers of migrants making landfall in the state during spring migration), fall migration is to many Floridians what spring migration is to those further north – the end of a period of relative bird paucity. Our summer bird fauna is the analog to their winter bird fauna. Of all of the neotropical migrants that pass through Florida in the fall, warblers are for me the glamour group. Don’t get me wrong – I get jazzed about any new arrival, but nothing gets me as excited as seeing and photographing warblers.

It’s pretty simple, really. Bright colors, high diversity, and the challenge of identifying immature and female birds all combine to make this family my favorite. Adding to their allure is the fact that warbler migration is such an extended phenomenon, lasting from mid-summer until nearly true winter. The seasonal trends in abundance of the different warbler species passing through or wintering in Florida are as diverse as the birds themselves.

Common yellowthroat male. This is most likely a first-winter bird based on the somewhat poorly defined mask.

We are now in the midst of what I consider to be the second wave of warbler migration – the influx of migratory populations of common yellowthroats into the state. I saw my first migrant common yellowthroats a little over a week ago, and this morning at Tiger Bay State Forest, they were the most abundant of the warbler species. Their numbers will continue to rise for the next week or two.

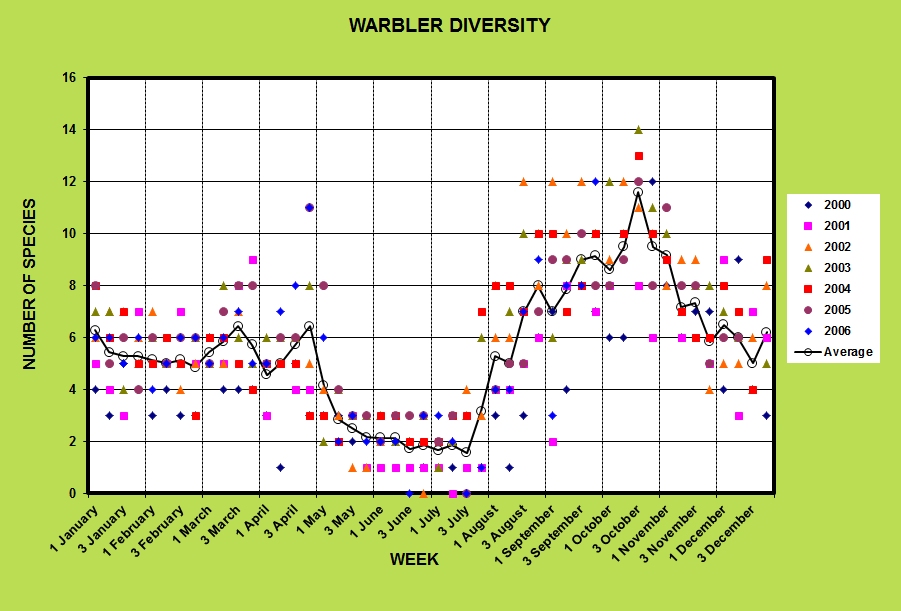

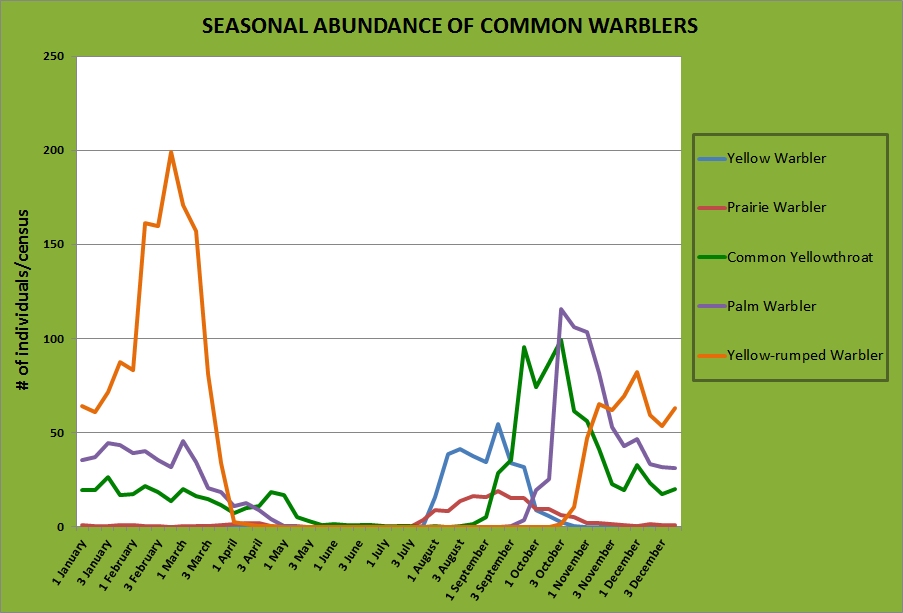

Although 43 species of warbler can be found at one time or another in the state (this includes the most likely extinct Bachman’s warbler), warbler migration in the peninsula is dominated by a relatively small number of species. In my experience, fall warbler migration can be categorized as a series of 4 waves of birds passing through the state at different times. The figures below are based on data I collected at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area in Lake County between 2000 and 2006, and should be interpreted with some caution – they are certainly not representative of the entire state, or even the entire peninsula. Any general conclusion is only as good as the sample it is based on, and my bird censuses at Emeralda constitute a biased sample. I think it’s a fairly decent proxy for warbler migration through the interior of the peninsula, since the 7000 or so acres comprising Emeralda contain a decent variety of many of the terrestrial and wetland habitats in central Florida. But not all major habitat types are represented – scrub, sandhills, and flatwoods are all absent from Emeralda, for example. Although ovenbirds were regular fall migrants at Emeralda, I never saw them there in the numbers there that I sometimes find in other upland habitats like scrub. It also seems clear to me that there is a fundamental difference between warbler migration at some coastal locations and those inland. In the seven years I did weekly bird censuses at Emeralda, I rarely encountered some warbler species that can at times be fairly common at coastal locations; this group includes species such as hooded and worm-eating warblers.

Seasonal abundance of the five most common warbler species at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area in Lake County. I found around 25 species of warblers there over the years, but these 5 were far and away the most abundant.

The first wave of warbler migration at Emeralda begins in late July, and peaks in September, and is due to two species with roughly similar timing of passage – prairie warblers and yellow warblers. I’ve mentioned the spectacular numbers of yellow warblers during fall migration at Emeralda in a previous post, emphasizing that the high daily counts (over 100/day on good days) are probably somewhat unique to the specific combination of habitat characteristics there. Prairie warblers are much more generalized in habitat choice, and can be abundant early in the fall migration period in just about any habitat, including scrub.

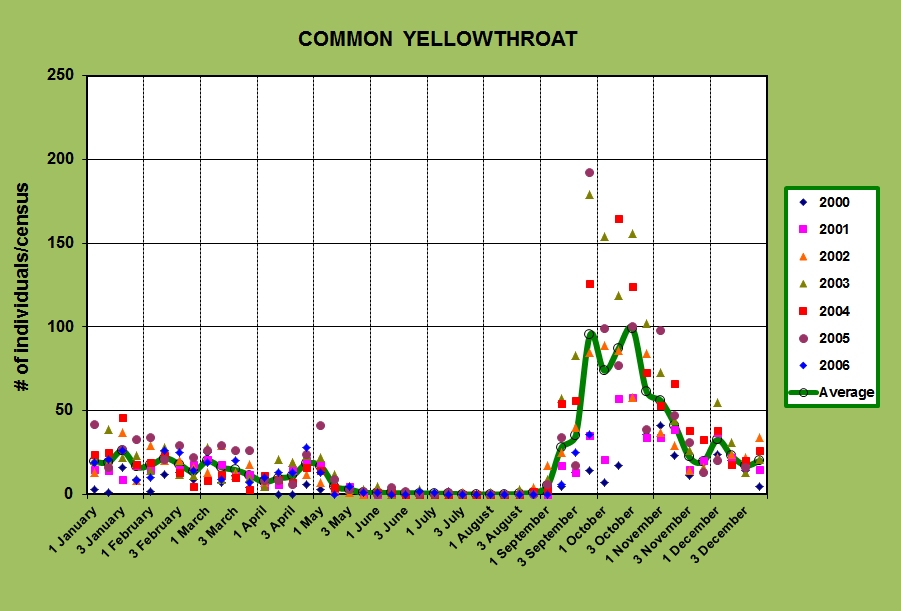

The second wave is just beginning – the arrival of the common yellowthroats. This species is particularly interesting to me because it is one of the few warblers that breeds in Florida. Though fairly catholic in choice of breeding habitat (ranging from freshwater marsh to pine flatwoods), the population of breeding birds is dwarfed by the influx of migrant birds from northern populations, as seen in the graph below.

The third wave occurs in another couple of weeks – the arrival of the palm warblers, many of which will spend the winter in the peninsula. I’ve been hearing reports of small numbers of palms showing up in the last week or two, though I haven’t seen any yet.

Finally, the fourth and final wave is the appearance of the yellow-rumped warblers, which will begin appearing in late October and continue to increase in numbers for the next several weeks. Butterbutts will become so abundant that they totally dominate the wintering warbler community, much to the displeasure of some birders. Picking through a flock of dozens or hundreds of yellow-rumps in attempt to find something “good” hidden amongst can be a challenge. The appearance and ascendance of the yellow-rumps also marks the end of major warbler influx into the state.

It’s hard to harbor negative feelings about the super-abundant yellow-rumps, though. While birders in most of eastern North America are pleased to find a handful of yellow-rumps on a winter birding trip, winter birders in Florida can count on finding as many of them as we could want, along with smaller numbers of 6 or 7 other warbler species on a good day. And that ain’t too shabby.