March 30, 2014

All real biologists love Charles Darwin, or Saint Chuck as he is sometimes known among the fraternity. Darwin’s genius was multifaceted; he was first and foremost a naturalist, and a damned fine one at that. In addition to his monumental bestsellers, The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man, Darwin wrote numerous books about more obscure biological topics, such as the sex lives of orchids, the role of earthworms in soil formation, and the emotional responses of humans and animals, among others. His fascination with the patterns of distribution and morphological diversity of the Galapagos finches (“Darwin’s finches”) is said to be one of the key observations that led him to his revolutionary evolutionary insights.

His greatest contribution to biology, though, was his elucidation of the principle of natural selection, and later, sexual selection. Darwin was certainly not the first scientist to suggest that organisms evolve and that one species can transmogrify over time into a new and radically different form. The Greek philosopher Anaximander is often credited as being the first to suggest that organisms evolve, way back in the 7th century BC. But Darwin (along with Alfred Russell Wallace, who tends to get lost in the mix), was the first to propose a credible and testable mechanism explaining how evolution and adaptation happen.

American goldfinches show tremendous sexual dimorphism (different appearance between males and females) during the breeding season, but not much during the winter. Males aren’t much brighter than this basic-plumage female.

Darwin’s principle of natural selection is surprisingly simple, and to those enchanted with biotic diversity and natural history, incredibly powerful as a tool for understanding. The process of natural selection is based on a few widely confirmed premises: a) individual organisms vary in many traits, b) variability among individuals in traits is heritable (i.e., traits have a partial genetic basis), and c) variability among individuals in these heritable traits results in differences in performance in the natural world. Most importantly, individual variability affects the ability of individuals to survive and ultimately reproduce. Those individuals who are more successful at reproduction will pass more of their genes to the next generation than individuals that reproduce less or not at all. Over the course of generations, the genetic composition of the organism will change. That’s evolution. The widely used term “survival of the fittest” does a very poor job of capsulizing the process. Natural selection is not so much about survival as it is about the ability to produce viable offspring carrying one’s genes, though successful reproduction does require that an individual survive until at least the age of reproductive maturity. Ultimately, though, difference among individuals in reproductive success, or Darwinian fitness, is the defining feature of Saint Chuck’s principle.

The mottled appearance of this male clearly shows old (basic) plumage being replaced by new (alternate) plumage. The black cap of males is only present in the alternate plumage.

Evidence for the basic premises of natural selection is overwhelming, and obvious to anyone who spends any time studying organisms and how they function in their real environment. Right now in Florida, evidence for one of those premises is obvious to anyone who maintains feeders that attract American goldfinches. Individual variability among goldfinches is on full display right now as they begin preparation for their northward migration and breeding season. It is a challenging task to find two birds that look exactly the same right now.

Though individual variation in many traits exists in all bird species all the time, often it’s not apparent to dull-witted human observers, though I have no doubt it is obvious to the birds themselves. They know who they are. I absolutely adore the American crow family that visits my yard frequently, but except for the patriarch with a slight bill deformity (Longbeak, or LB), I can’t tell them apart, aside from the crude distinction between adults and younger birds that still show hints of brown in their plumage.

American goldfinches are undergoing their pre-alternate molt right now, and males are making the transition from their dull, female-like basic (winter) plumage to their alternate (breeding) plumage. Each male is on his own schedule, slightly or greatly out of sync with his mates. Some males have scarcely begun their pre-alternate molt, while others have nearly completed it. This in turn reflects tremendous variability in a panoply of physiological states correlated with the progression of molt, likely including serum testosterone levels in their blood. A rapid increase in serum testosterone levels in males during late winter and spring is a common phenomenon among birds breeding in temperate habitats; rising testosterone strongly influences a wide range of traits, including both plumage traits and reproductive behaviors like singing, male-male aggression, and in many species, territorial behavior.

But why is individual variation in progression of molt so apparent in goldfinches, but not so much in other species? As it turns out, American goldfinches are unique in a number of aspects of their molting and reproductive behavior. They are the only species among their close relatives (cardueline finches) that undergoes a complete replacement of body feathers in the pre-alternate molt. Consequently, the magnitude of change between basic and alternate plumages of males is unusually large. The mottled appearance of many males, who have patches of new bright yellow contour feathers interspersed among the remaining duller basic plumage, makes each male slightly (or greatly) different from others.

Although American goldfinches don’t typically breed in central Florida, this alternate-plumage male appeared at my feeders, along with a female, in August of 2012, when goldfinches are usually still nesting. Interesting color variation in this male as well – he had no white feathers in the wings.

Asynchrony in the progression of molt among males is accentuated by their extended molting period, which can occur between March and July. At the time when most temperate passerines have finished breeding or are working on a second or third brood, American goldfinches are just getting ready to nest. They are one of the latest breeding species in eastern North America, with nesting activity mostly occurring in June through August. This may be related to their dietary specialization – they are among the most devoted seedeaters of any North American passerine. Many species that feed heavily on seeds during the winter, such as sparrows, switch to much greater reliance on insects when nesting, as animal prey provides more protein to the growing nestlings than seeds. American goldfinches, by contrast, feed their offspring primarily seeds, and in particular, they are addicted to the seeds of various species of thistle. Their relatively late breeding season may be an adaptation to the reproductive phenology of thistles – goldfinches don’t initiate breeding until thistles are blooming and setting seed. The young birds hatch at a time of maximum thistle seed abundance. This delayed breeding behavior may allow them to extend their pre-alternate molt over a longer period than most temperate passerines, allowing a much greater amount of asynchrony in molt than is seen in most other birds.

News flash – goldfinches love thistle seed. The Nyjer seed sometimes sold as “thistle” seed for feeders is not really a thistle, but another composite called Guizotia abyssinica. This is the Florida native Cirsium horridulum, an early-blooming thistle that will set seed and provide food for wintering goldfinches before they migrate.

Male American goldfinch feeding at heads of Cirsium nuttalii, a native thistle that blooms and sets seeds before the migrating goldfinches have departed.

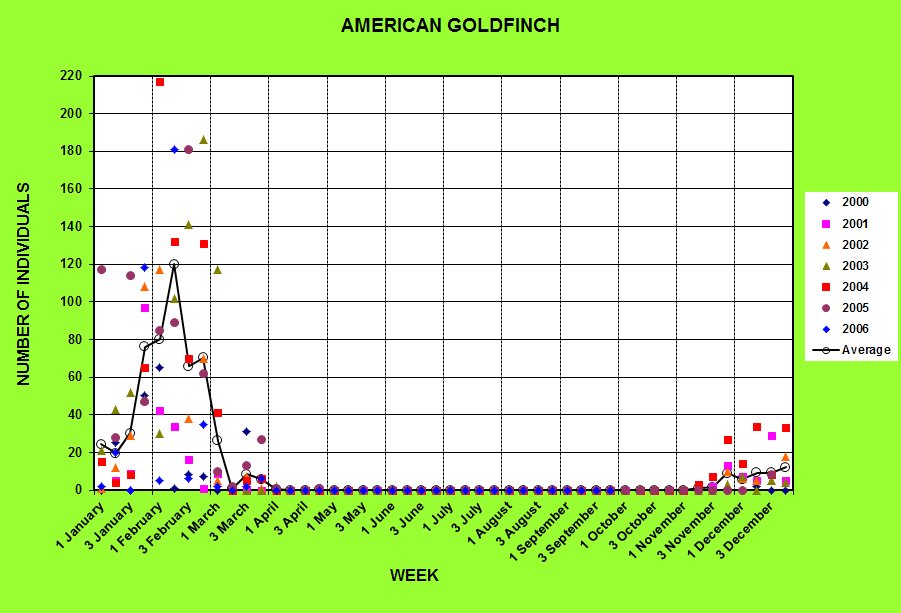

In Central Florida, American goldfinches are relatively late migrants. I don’t usually see them until November. During the 7 years I did weekly bird censuses at Emeralda Marsh, I saw them in small numbers beginning in mid-November, but didn’t see large numbers until late January and February, when flocks of hundreds of birds could be found feeding on the elm fruits that were just maturing. Goldfinches are typically quite nomadic in the winter, traveling widely in search of their favored seeds. During most of the winter, I usually have no more than a half-dozen birds at my feeders, but in late March and April their numbers skyrocket. I have somewhere around 30-40 birds visiting my feeders right now. Perhaps some of this increase in numbers late in winter is due to depletion of natural seed crops.

So with all these birds around, massive individual variability in appearance, and physiology, of American goldfinches is apparent. What are the consequences of this variation in molt and appearance to the reproductive success (Darwinian fitness) of individuals? It seems like a safe assumption that differences in plumage characteristics are heritable, as they are in other birds whose genetics are well known. But is there a significant impact of differences in the timing of molt on the ability of males to obtain a mate and successfully reproduce? That’s a good question. Some evidence suggests that pair-bond formation may occur in pre-breeding flocks, so differences in plumage among males could be having their initial effects on reproductive success right now.

Keeping that plumage in peak condition requires a lot of maintenance. When the goldfinches aren’t devouring the seed in my feeders, they are usually roosting in a nearby oak, preening and loafing.

In American goldfinches, males winter, on average, further north than females, and precede them in their arrival at breeding habitats by about 2 weeks. Males that molt earlier may also migrate earlier, allowing them to claim the best breeding sites. In some other passerines, like American redstarts, research has shown that higher-quality males are the first to return to their breeding habitats, and they are able to stake out the highest quality territories. Does it work that way in American goldfinches as well, even with their delayed onset of breeding? Maybe. It bothers me a bit every year that I almost never see males that have fully completed their pre-nuptial molt; even the most brightly colored males usually have at least a few small patches of basic plumage remaining. Perhaps the males that have completed their molt are already winging their way north.

Male American redstarts that arrive first on breeding grounds are high-fitness individuals who get the best territories.