May 31, 2014

I do most of my birding and natural historizing locally, only occasionally traveling more than 30 miles to a birding destination. Once a year, though, I drive to northern Virginia sometime in May to hang out with my father for a week or so and experience the explosion of breeding bird activity in that part of the country. One of the rewards of making this pilgrimage is the opportunity to experience new behaviors of species that winter, but don’t breed, in Florida. There are a lot of those. Although I mostly grew up in northern Virginia, and discovered my obsession with birds there, I’m still surprised on most visits by finding species or seeing behaviors that I somehow missed while I was living there. Cedar waxwing breeding behavior is a case in point.

In the last couple of years, I’ve started visiting a new site while in Virginia – a county park that was only recently opened to the public. Silver Lake Regional Park, in Haymarket, Virginia, opened in 2009, and has become one of my favorite birding spots when I’m in the area. At 230 acres, it’s a postage stamp of a park. Silver Lake is a 23-acre impoundment fed by Little Bull Run, and the surrounding piedmont is a mosaic of mostly disturbed and successional habitats. Breeding bird communities of so-called old field habitats in the mid-Atlantic region contain a number of charming birds, and the diversity and density are high enough that during May there is nearly always something happening worthy of watching. At Silver Lake, there is a large parking area that is designated for horse trailer parking, which abuts a lovely tract of perhaps 20-30 acres of prime old field habitat in the shrub-sapling stage of succession. I rarely see anyone else at this end of the park; most park visitors cluster around lovely Silver Lake to fish. So I have this beautiful shrubby old field all to myself.

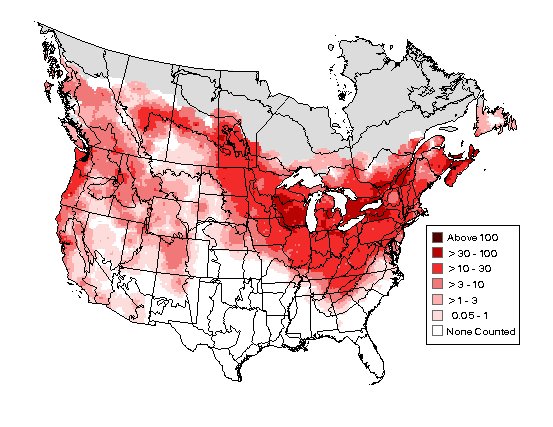

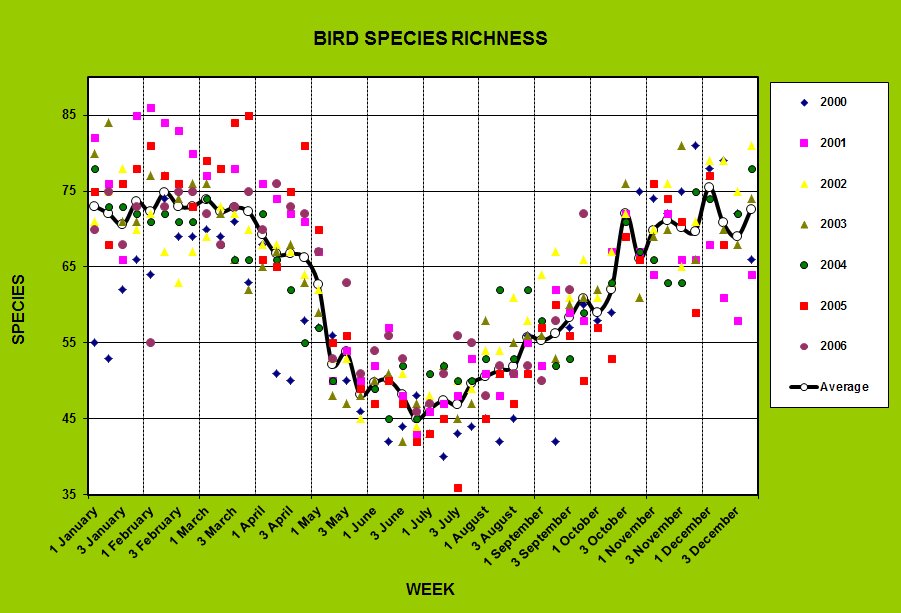

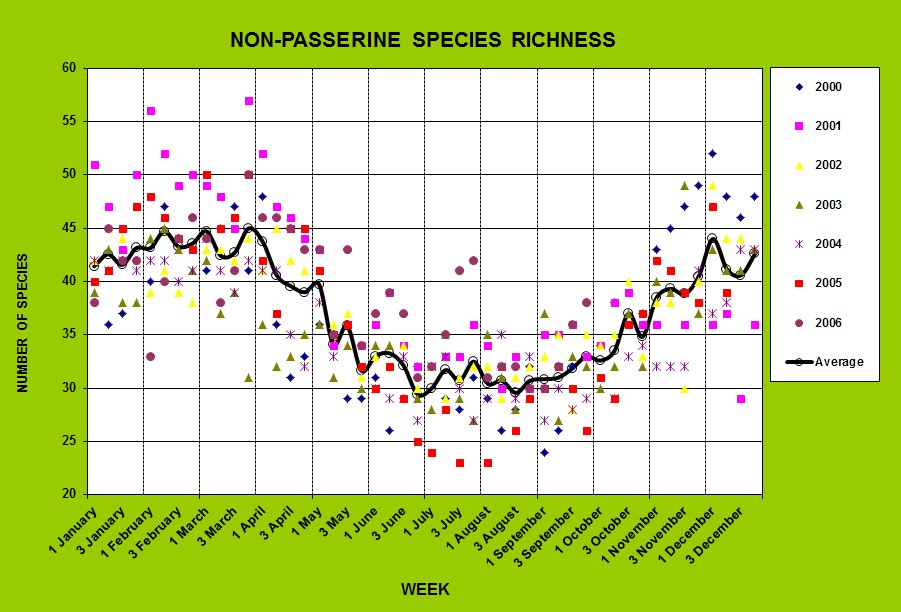

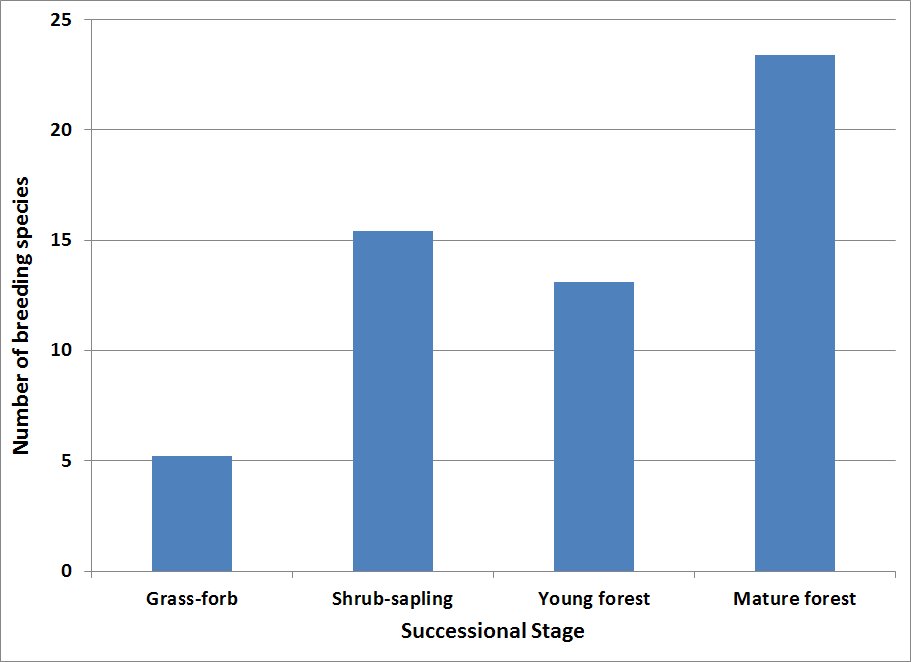

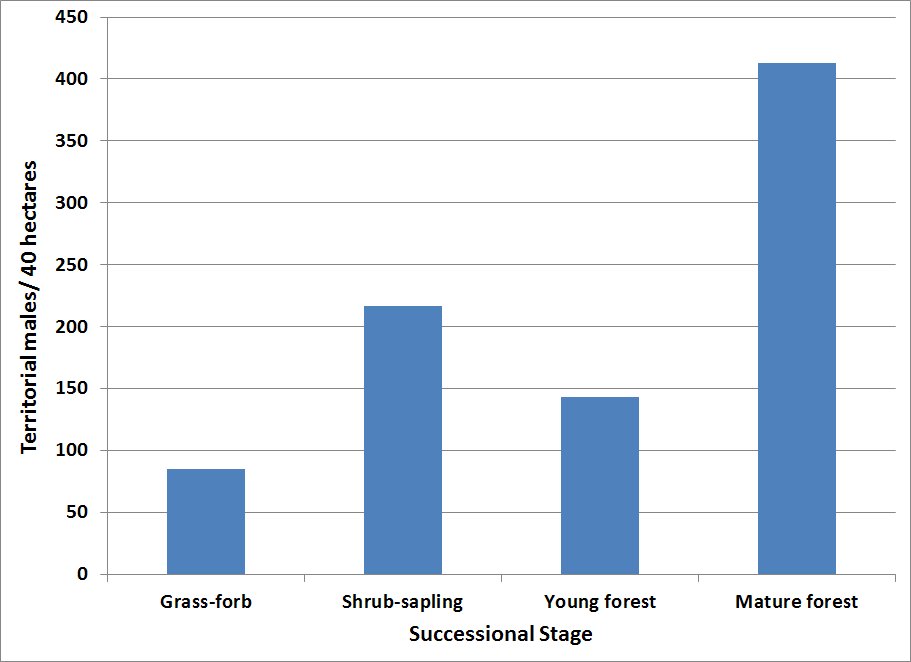

When agricultural land is abandoned and allowed to revert to a natural state, it undergoes a predictable sequence of changes in plant composition, vegetative structure, and characteristic breeding bird communities, called secondary succession. The first few years of succession are characterized by low stature vegetation consisting entirely of herbaceous grasses and forbs; because of the simple, monolayer structure, the breeding bird community is low in diversity, often consisting of only a few species (grasshopper sparrows and eastern meadowlarks, for example) at relatively low densities. Within 5-10 years, woody plants begin to invade and become a prominent component of the vegetative structure; these invaders include species such as red cedar, wild cherry, and persimmon, among others. The increase in vegetative complexity, and concomitant increase in the amount and variety of food resources for birds, results in a big jump in breeding bird diversity, as species like indigo buntings, blue grosbeaks, song and field sparrows, brown thrashers, common yellowthroats, and yellow-breasted chats establish breeding populations. The density of breeding pairs also increases nearly three-fold between the grass/forb stage of succession and the shrub-sapling stage. All of the various stages of succession from abandoned field to mature deciduous forest have their own characteristic bird communities; diversity and density of breeding birds is greatest in late successional habitats, which in northern Virginia means various incarnations of eastern deciduous forest.

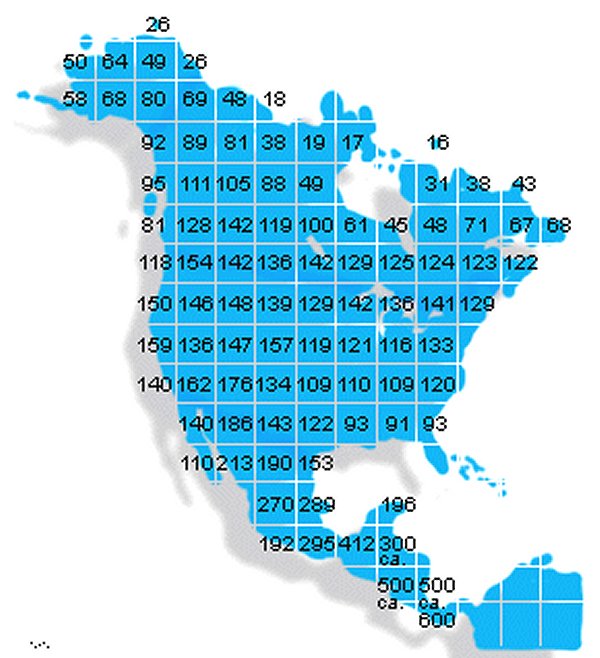

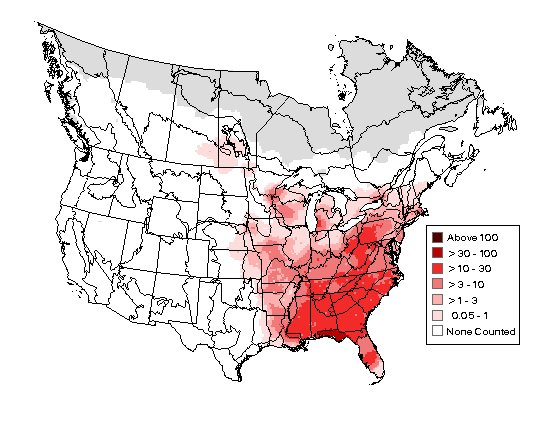

The average number of species breeding in four stages of secondary succession in the eastern U.S. (from May, 1982)

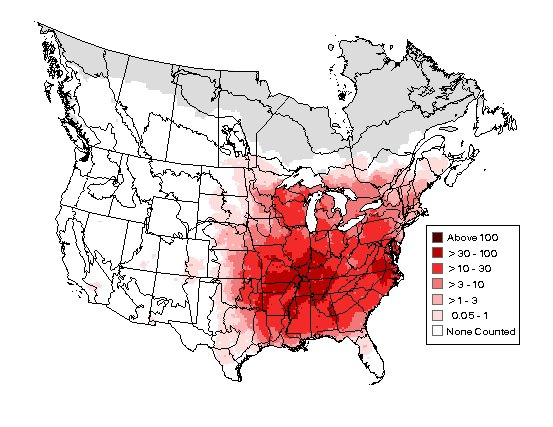

The density (number of territorial males/40 hectares, or about 100 acres) at four stages of secondary succession.

Density and diversity of breeding birds generally increase in a predictable pattern with successional age of the habitat, with the greatest abundance and diversity occurring in the so called “climax stage”, which remains relatively stable in plant composition unless it is disturbed by either natural events (fire, blowdowns, etc.) or anthropogenic causes (deforestation). In the mid-Atlantic region, the climax plant community in many parts of the landscape is some form of eastern deciduous forest. (The concept of a climax community that is stable and unchanging over long time periods is eschewed by many ecologists; it’s a pretty simplistic idea.) So even though it’s not the most diverse habitat type in the successional continuum, the shrubby stage of old-field succession is hard to beat for superb birding. Not only are many of the birds breeding there interesting and beautiful, the relatively low stature of the vegetation and open architecture of the habitat make observation of bird activity far easier than in the more diverse mature forests.

Oak-hickory-beech forest is the terminal or “climax” stage of succession in parts of northern Virginia.

So on two of the five mornings I was in Virginia, I found myself at Silver Lake Regional Park, ensconced in my car (a blind of sorts) to just sit and soak in the stunning beauty of spring in Virginia. The primary object of my attention was the yellow-breasted chats that breed in this patch of habitat; I see chats only rarely in Florida, and then typically very briefly. There are few bird species skulkier than a yellow-breasted chat. That doesn’t change all that much when they are breeding, but they are such vocal birds that even if you can’t see them much of the time, you can keep track of their movement and activities by the nearly constant outpouring of croaks, grunts, whistles and other varied mechanical sounds these oversized warblers produce. They do a killer imitation of a distant crow cawing; on several occasions, they momentarily fooled me with this call even though I knew I was listening to a chat. They’re that convincing. On my first visit to Silver Lake, I had a remarkable half-hour or so watching and listening to yellow-breasted chats that on occasion abandoned their skulkitude and FULLY EXPOSED THEMSELVES. Amazing.

So it shouldn’t be hard to understand how I can easily pass an hour or two sitting by this patch of old field habitat, watching and listening to the comings and goings of the breeding birds. It was while I was doing just that on my second visit, parked next to a small copse of some fruit-bearing sapling, that I saw a pair of cedar waxwings fly into the dense cover at the back of the grove, nearly hidden from sight. Cedar waxwings are a species that I saw fairly regularly when I lived in Virginia, but always as nomadic flocks of fruit-scouring pirates during the non-breeding season. At Silver Lake, though, they seem to be common breeders. I had discovered a nesting pair of waxwings frequenting a dense clump of vine-tangled cedars on my first visit to Silver Lake, but those birds were in such dense cover that they were nearly impossible to observe when they were on or near the nest.

By contrast, this pair of waxwings in the little grove by the parking lot put on a show for me. One of the birds, presumably the male, flew out of the back of the clump towards me, and snagged a pair of small, green fruits. He was soon joined by his mate, and they began a ritualized behavior that was entirely new to me. The male presented the unripe fruits to the female, which I interpreted as courtship feeding. Cool to see, but not particularly unusual. Many passerines and non-passerines perform similar ritualized feeding during courtship and pair-bond maintenance. I see it every summer between the cardinals that breed in my neighborhood. But the female didn’t eat the fruits – she moved away from the male a few inches and held it, then moved back to the male and passed it back to him. He held them for a few seconds, then returned them to the female. She followed suit. For the next minute or two, they repeated this behavior at least 5 times. Eventually one of the waxwings flew away; I don’t know if it was the male or the female that left first, or if he or she even ate the fruits. It was a trip to see.

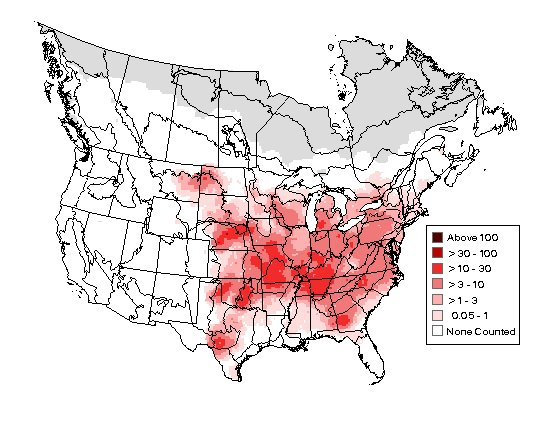

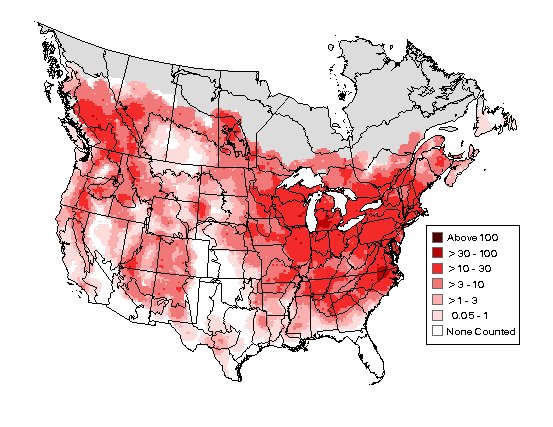

Waxwings show a number of distinctive aspects of their breeding behavior. Anyone who has marveled at the antics of big flocks of waxwings wintering in Florida as they decimate the fruit crop on a chosen tree knows they are extremely social birds, and this extends to the breeding season. They aren’t territorial when breeding, and sometimes nest in loose colonies of 10 or more breeding pairs. Compared to most other passerines, they are among the latest to begin breeding activity. Eggs aren’t usually laid until late May or early June, which seems to be an adaptation for synchronizing the appearance of the greedy youngsters to the availability of ripening fruit. Waxwings are one of the few primarily frugivorous birds in North America; while many species feed on fruit opportunistically, none are as specialized to a fruit-eating diet as waxwings are. They do incorporate more animal prey into their diet during the breeding season, probably for the protein content, but still fruit makes up a substantial portion of the diet of nestling birds.

So this pair of birds engaging in repeated acts of fruit passing were likely still in the courtship/pair bonding stage of the nesting cycle. The entry for cedar waxwings at Cornell’s Birds of North America Online site gives this account of the behavior I observed:

“Typical courtship display in which mates alternately approach one another on a perch with hopping movements, sometimes touching bills. Usually initiated by male; successful when female reciprocates (Putnam 1949). This display is termed the Courtship Dance or Courtship-Hopping (Silloway 1904, Crouch 1936, Lea 1942). Courtship-Hopping begins in migrant flocks, and has been noted as early as Apr in California (Feltes 1936) and in Ohio (Putnam 1949). Courtship-Hopping often includes passing a small item (usually food item such as a fruit, insect, or flower petal, but sometimes inedible items, and occasionally object-passing may be merely simulated, with no object actually passed; Fig. 3) between male and female, interspersed with short hops away from and back toward mate. Display usually initiated by male, who obtains a food item and joins female at a perch (Putnam 1949). Male approaches female by hopping sideways and passes item to female with turn of head (usually both birds face same direction). Female typically hops away from male, then hops back and returns item to male. Male then responds by hopping away, often performing bowing movements between hops, before hopping back and repeating the sequence. The display may be repeated a dozen times or more (Tyler 1950) and is usually terminated when the female eats the food item (Putnam 1949). Bouts of courtship-feeding may be interspersed with fast circular flights around nest area. Crouch (1936) observed an apparent extension of passing behavior in which female would pass last food item back to male after he had delivered food to her, either at or away from nest. Then the mates would allopreen and bill. Copulation is usually preceded by Courtship-Hopping (Putnam 1949).”

Though I saw no allopreening, circular flights, or copulation, I was ecstatic about observing this fascinating behavior. One of the great joys of natural history study is knowing that even after observing a species, sometimes extensively, for years or even decades, there is always the potential for learning something new about them.

References:

May, P.G. 1982. Secondary succession and breeding bird community structure: Patterns of resource utilization. Oecologia 55(2): 208-216.

Witmer, M. C., D. J. Mountjoy and L. Elliot. 1997. Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/309