June 15, 2015

Every serious bird photographer who has been at it for a while has a nemesis bird or three. There’s a progression for the obsessed bird photographer – first you knock out all the easy stuff. You know, feeder birds, extremely common and cooperative stuff like yellow-rumped warblers, turkey vultures, ring-billed gulls, and so on. At some point, for many of us, then the compulsion turns into a quest to photograph all the birds of the region you spend most of your time in. An unattainable goal for most, but a tangible target nonetheless. Gradually the library of images grows, until you have acceptable images of most of the typical species. It’s a moving target, though; one problem is that the definition of acceptable is constantly changing as your proficiency increases (hopefully). So while your biggest pleasure is photographing a species that you have no images of, you’re constantly trying to upgrade the quality of the images of those species already photographed. And so it goes. You accept that the very rare or elusive species are distant dreams at best, but every now and again that improbable event occurs and you actually add one or two of those to your collection of bird images. Why do we do it? That’s a whole other question I’m not about to try and tackle; I really don’t understand it myself. It does take on aspects of mental illness after a while, though. How many hundreds of images of northern parulas and great blue herons do you really need? The only answer I’ve ever arrived at is more.

As beautiful as they are, some birds, like northern parulas, are just too easy to photograph to be a real challenge.

More vexing than the rare species though are the nemesis birds. Those are the species that aren’t particularly uncommon or hard to find, and of which you can find thousands of high-quality images on-line, yet they somehow elude your best efforts to add them to your list. The degree of consternation inflicted by these recalcitrant bastards is directly related to how long you have pursued them. In some cases it may be decades.

I have dozens of images of the larger American bittern that I’m pretty happy with; least bitterns are a different story.

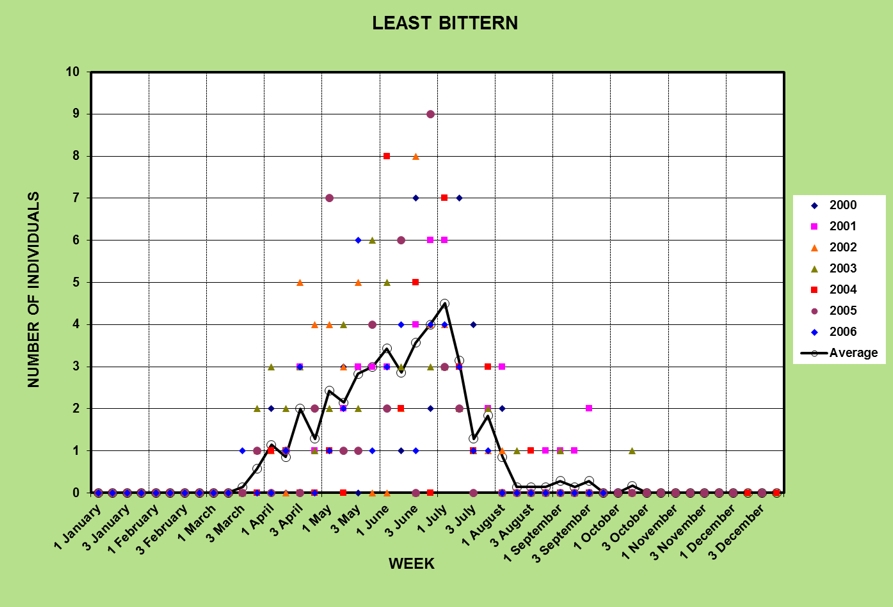

For me, one of the nemesis birds that has been at the top of my list for the decades I’ve lived in Florida is the least bittern. These elegant little birds, the smallest of the North American herons, are widespread as breeding birds in the ubiquitous wetlands of Florida. They occur as far north as Virginia, where I cut my birding and bird photography teeth, but I never saw them there. But in Florida, they are not difficult at all to find, or uncommon. Breeding densities as high as 15 pairs per hectare have been recorded. They do tend towards the skulky end of the behavioral continuum, though, which combined with their small size (12-14”, not much larger than a blue jay), can make them a bit of a challenge to photograph. But seeing them – hell, I see them all the time during the breeding season in the appropriate habitat. During the 7 years I did weekly bird censuses at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area in Eustis, which contains lots of good breeding habitat, I saw them regularly between mid-March, when most return from their winter home, and mid-October, when most of them have departed. During mid-summer, I would often see or hear 5 or more of these charming little waders on each census. Their departure each year, in which I once again failed to obtain a decent photo, always brought a bit of anguish, and a bit of hope that next year would be the one. An occasional oddball individual will overwinter in central Florida, but for the most part they are the typical birds of summer. By which I mean Florida summer, which runs from about March to October.So I never really entertained any illusions of photographing one outside of the breeding season.

This is no great blue heron, posing in every roadside ditch for any yokel with a point-and-shoot. (No offense to the yokels with point-and-shoots out there.) You have to go looking for them, and then you have to find one close enough (which is pretty damned close for a bird that small) and exposed enough for a decent photo. Needless to say, that particular set of conditions eluded me for so long. Oh, sure, I got photo ops on occasion. I have several dozen transparencies (also called slides, for those digital natives unfamiliar with the concept of film) with recognizable least bitterns on them. But in all, they are small in the frame, and none of them captured the essence of least bittern.

Seriously, any twit with a pinhole camera can get stunning closeups of great blue herons in Florida. Which is not to say that I don’t still photograph them on occasion. What can I say – I’m a high-tech twit.

These are amazing little birds to watch, if one is fortunate enough to see one foraging for any period of time. On the continuum of foraging strategies of herons and egrets, ranging from the nearly immobile ambush foragers like great blues to the maniacal pursuit foragers like reddish egrets, least bitterns are somewhere in the middle. They can be frozen for extended periods, intensely peering at a couple of square inches of habitat until a prey item comes into range, but they can also be relatively active, changing perches every minute or two until they find the right spot. Acrobatic little fuckers they are as well, hanging upside down from a narrow perch above the water, extending their telescoping necks in an instant to snag the dullard mosquitofish that fails to notice this pendulous beauty.

So yeah, I have a handful of old, mediocre images of least bitterns, a couple of which I thought were pretty decent at the time I took them. The advent of the interwebs totally recalibrated my concept of what constitutes a decent image, though. Once I began seeing the high-quality images so many other photogs were able to obtain of this handsome little heron, my evaluation of my own images plummeted. One of my favorite images, at the time, was of a recently fledged youngster sitting on his haunches in the middle of Airstrip Road, surrounded by shellrock, with a few wispy tufts of down feathers still remaining on his adorable little noggin. But this slide, like all my others, failed to meet one of my prime criteria for a good bird shot – you need a level of resolution allowing discrimination of barbs of individual feathers. My old slides all failed that test.

Even after I went digital, which makes bird photography an order of magnitude (at least) easier than the primitive film technology, good least bittern images still eluded me. I made a couple of trips during the breeding season to the celebrated Viera Wetlands in Brevard County, a site from which I had seen dozens of superb least bittern photographs posted on-line. I saw them there, but never got anything approaching the type of image I had in my mind.

I was moderately satisfied with this “in-habitat” shot of a least bittern from Viera Wetlands, but it wasn’t really what I was hoping for.

The closest I had come to a satisfactory close-up of a least bittern prior to yesterday’s outing, also from Viera Wetlands.

So I’m pleased as punch, as the happy warrior Hubert H. used to say, to report that my quest for decent least bittern photos has turned the corner. I’m also happy to report that this happened at my new favorite bird photography site, the Lake Apopka Restoration Area wildlife drive. On my first visit a few weeks ago, I thought this magnificent site should be full of least bitterns, but didn’t actually see or hear any until my second or third visit. A couple of weeks ago I actually got some marginally acceptable ops with a least bittern perched in a willow tree. The photos were by far better than anything I had previously, but the light was less than optimal (a totally overcast morning, the bird strongly backlit by a featureless white sky), and it was a bit too distant to reveal the kind of plumage details I consider requisite for a good bird photo.

Yesterday, my chakras aligned. The bird gods smiled. I got lucky. Interpret it as you see fit. It was a sunny morning, bird activity was everywhere along the wildlife drive, and around 8:00 a.m. while the morning light was still sweet and rich, I spotted a least bittern feeding from some dead stems of some emergent woody plant in a shallow impoundment. And it was relatively close to the road. Somewhat incredulously, I slow-rolled towards the little dude, expecting it to bolt into deep cover long before I was in photo range. But he didn’t. I slowly pulled up to where he was feeding, with the light coming from directly behind me (point your shadow at the bird, says the bird photog guru Artie Morris), and he cared not a whit. Heart pounding, adrenaline pumping, I feverishly began photographing. After a minute or two, the least beast decided to move, flying to a new perch 30 or so yards behind me. But still close to the road. I backed up slowly, and once again he stayed for a few moments, allowing a few more shots as he moved from perch to perch before finally disappearing into dense cover.

I was totally juiced. It’s fair to say that if I hadn’t taken another photo or seen another bird that morning, I would have considered it a morning very well-spent. As I drove on along the wildlife drive, I was savoring the moment when I could look at those images on the big screen and begin editing them. There’s something incredibly rewarding about capturing even one series of decent images relatively early in the morning; it doesn’t really matter what the rest of the day brings. You know you already have some images you’re going to be pleased with. Of course there’s always that bit of the neurotic in me that begins the second-guessing game – what if I did something wrong, or missed critical focus? Even after chimping the images like a demented fool my fears are never completely allayed. You can only judge image quality so far by viewing them on the LCD screen of the camera. You have to download them and view them large to really make an accurate assessment.

Cooperative least bittern number two, perched on one leg, with the other tucked up into his belly feathers. Even closer than the first.

So I was a pretty contented dude at that point. But that wasn’t to be my only bittern buzz of the day. Not more than 15 minutes later, I spotted another, sitting completely exposed on a dead branch, in perfect front light. Even closer than the first. And once again, I was amazed as I slowly rolled up on him and he sat perfectly still. I shot this guy for 4-5 minutes as he mostly did nothing other than check me out occasionally. At one point he dropped the foot that he had tucked into his belly feathers, turned around, hunched forward, and expanded his throat and chest as he began calling with the sweet cuckoo-like call that is the easiest way to detect the presence of these tiny ardeids. I was in a state of absolute euphoria as I filled a memory card. Hundreds of images varying only in the slightest degree, the vast majority of which would never be seen by anyone like me. But what did I care? A nemesis bird had been forever removed from the list.

A vertical shot, still on one leg. When you’ve got a bird posing for you like this, it’s hard not to go batshit crazy.

Can the crested caracara be far behind?