Sunrise in the scrub. Forest Road 46, Ocala National Forest

May 10, 2014

I find being in big expanses of native habitat around sunrise has the effect of producing brief moments of clear-headed thinking. For me, this is especially true of the more open habitats, like early stage scrub, where you can easily track the incremental effects of the ascending sun as the surging morning light progressively highlights newly visible features of the environment. I was sitting in just such a dense patch of oaky scrub in the Juniper Prairie Wilderness area of Ocala National Forest on Wednesday when one of those rare moments of lucidity raced through my normally muddled brain. I kid you not that I was actually sipping my tea when I heard the clear whistle and trill of drink-your-tea coming from the dense scrub. At that moment, I realized that I had made a foolish and easily refutable claim in my last post, in which I pondered the absence of breeding sparrows in most Florida habitats. I claimed that for the most part Bachman’s sparrow was the only breeding species in most inland or upland habitats of the Florida peninsula.

As it turns out, Bachman’s sparrow isn’t the only widespread breeding sparrow in the Florida peninsula.

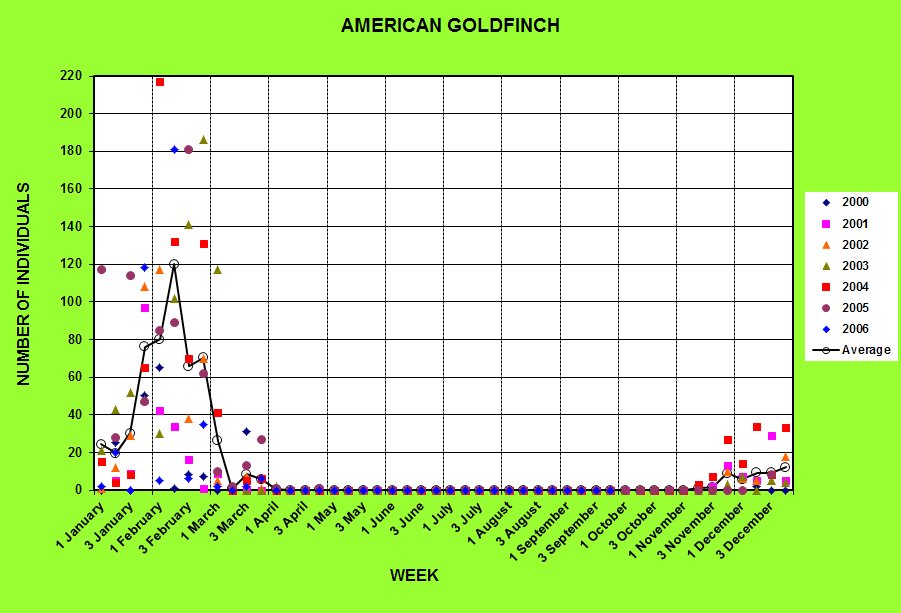

Astute birders and natural historians no doubt immediately recognized the fallacy of that statement – there’s one species of sparrow that breeds in a variety of habitats in peninsular Florida, and can be incredibly abundant in some, including scrub. Towhees are sparrows, really. We just don’t call them sparrows. A bit larger and more conspicuous in plumage than the typical cryptically-hued sparrow-type sparrows, but members of the same family (Emberizidae) nonetheless, and classified within that family as belonging to the same clade as the New World sparrows. In most respects, their ecology is similar to that of the smaller sparrows – they are omnivores, feeding more on seeds and plant-derived foods during the fall and winter, and switching to more of an animal-based diet during the breeding season when their voracious offspring need more protein than is available in most plant foods. They are fond of open or early successional habitats, though in Florida they nest in open-canopy woodlands like flatwoods or scrub as well. Eastern towhees were by far the most common breeding birds I heard in most areas of the Juniper Prairie Wilderness scrub on this beautiful May morning.

Drink your tea, he said. I was way ahead of him.

The juvenal plumage of eastern towhees clearly shows their affinity to sparrows.

So we do have a common breeding sparrow in many peninsular Florida habitats. But that doesn’t really resolve the conundrum – in some ways it magnifies it. If this one species of emberizid can successfully maintain viable populations here, why not the other sparrows with which it frequently co-occurs in breeding bird communities further north? It’s not hard to find towhees nesting along with other species typical of the shrub-sapling stage of old field succession, such as song and field sparrows. The enigma is further confounded by the fact that field, song, grasshopper, chipping, swamp, and several other rarer sparrows (Henslow’s, LeConte’s, Lincoln’s) can be found wintering in these habitats in Florida. But none stay to breed. Why not?

Field sparrows winter in peninsular Florida, but don’t stay to breed here.

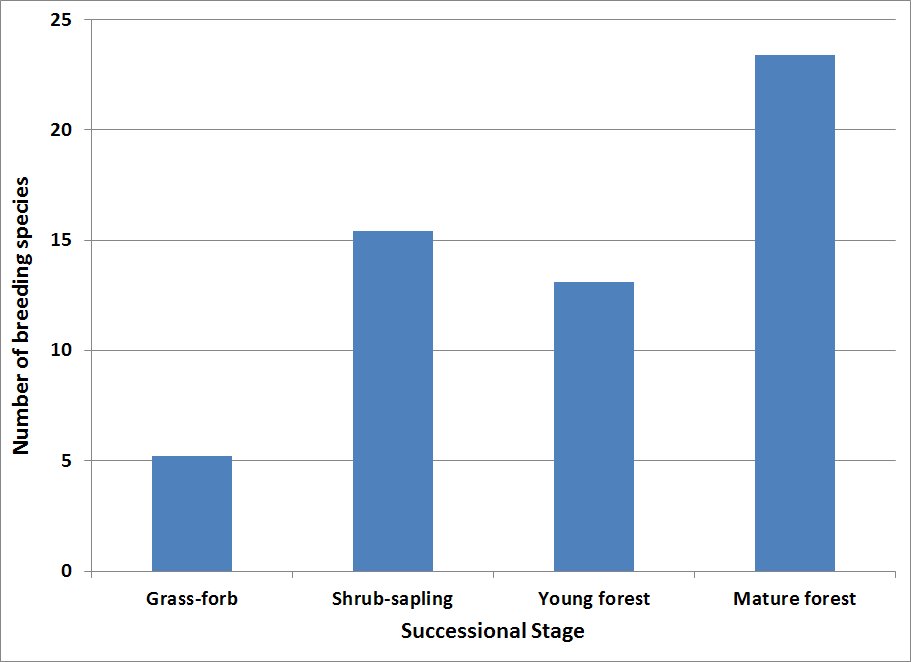

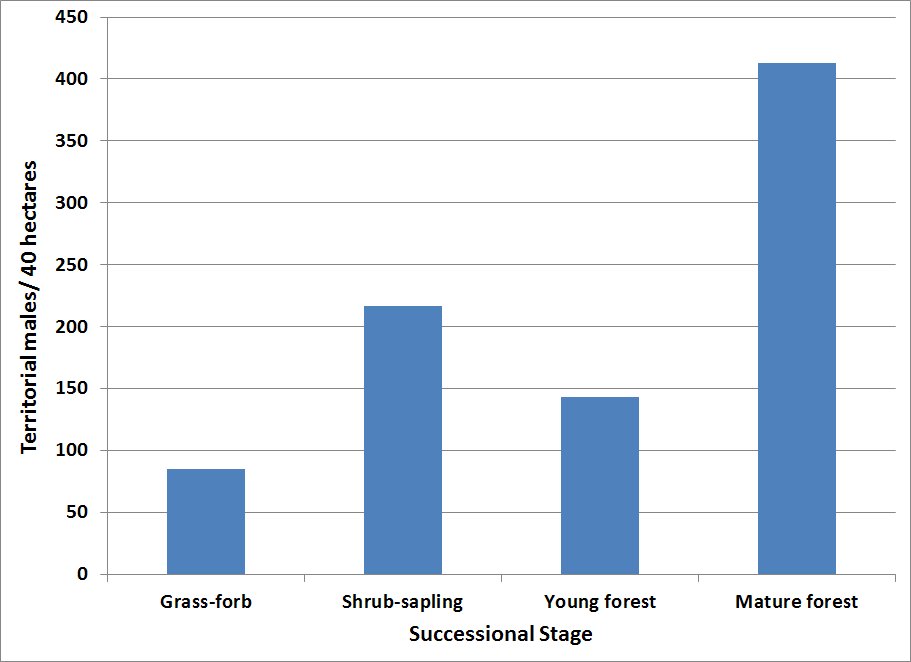

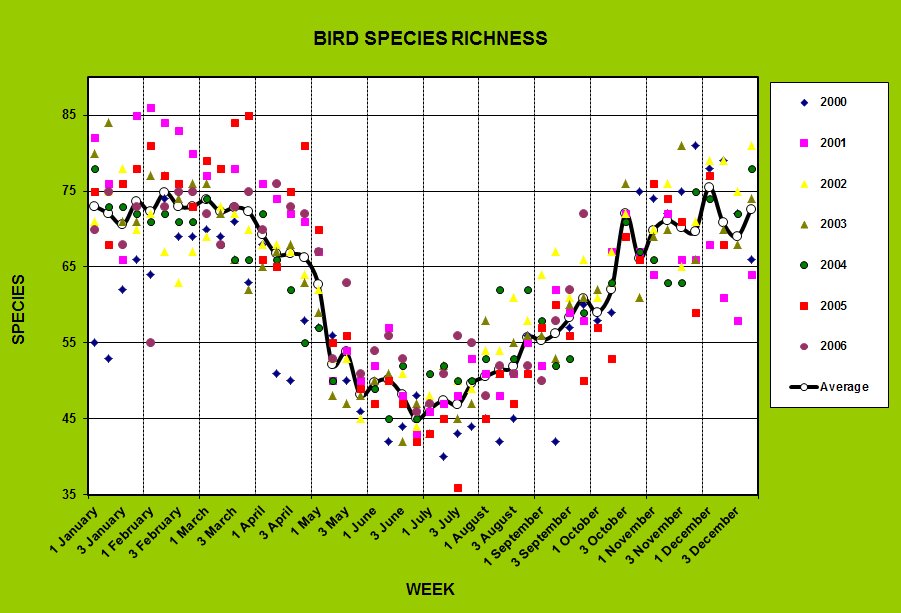

The sparrow problem is just one component of the riddle of peninsular Florida’s low breeding bird diversity. One of the most well-documented trends in landscape ecology is the profound latitudinal gradient in species diversity among a wide range of taxa – as you move from the temperate zones towards the tropics, the number of species of many, many groups of organisms increases dramatically. Though this pattern is widely known, it hasn’t been clearly explained in terms of an underlying cause or mechanism. More than a dozen hypotheses have been suggested to explain the higher diversity in the tropics, but none is universally accepted, and in fact most of the hypotheses are not even mutually exclusive. Like many complex ecological phenomena, the origin of these diversity gradients is probably multifactorial, arising from a number of interacting factors and causes. Higher productivity, greater climatic stability, a longer evolutionary history, greater importance of biotic interactions such as competition, predation, and parasitism – all of these and many more may contribute to the higher tropical diversity. But despite the fact that Florida is at a lower latitude than most of North America, and might therefore be expected to have higher bird diversity than areas further north, at least for breeding species of land birds that isn’t true. The picture with respect to breeding bird diversity in eastern North America is more complex and perplexing.

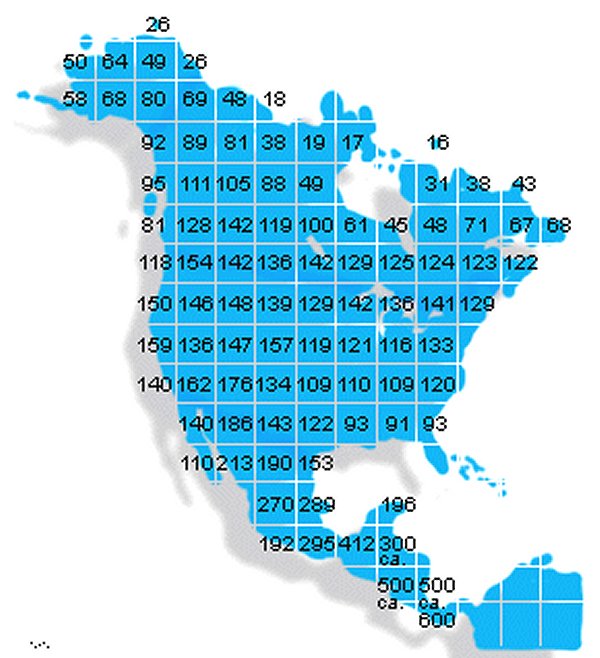

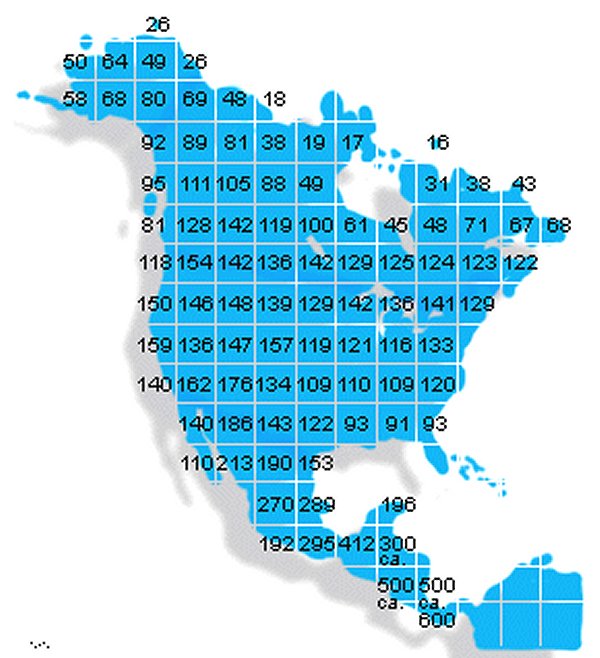

Number of breeding land bird species in North America, from a paper by Cook (1969).

The figure above, originally published in a 1969 Systematic Biology paper by R.E. Cook, contains a wealth of head-scratching trends in diversity. I first saw this figure in Eric Pianka’s classic little book Evolutionary Ecology over 30 years ago, I think, and it has taunted me ever since. This map shows the number of breeding land bird species in 300-square mile blocks, and even at this crude level of resolution, the contradictions and puzzles are enough to make me swoon. If you focus on the numbers of species breeding in the middle of the continent, starting in the prairie provinces of Canada and working towards Mexico and Central America, the temperate-tropical diversity gradient is apparent. But to the east, something funky is going on. Diversity actually is greatest at higher latitudes. In particular, notice the column of blocks that includes Florida – there are 141 breeding species in the region of the Great Lakes, but in the southeast block that includes Georgia and North Florida, there are only 93 breeding species. Though there is no number for the block that contains peninsular Florida, by my reckoning that number is about 72. I’ll repeat my previous claim – breeding bird diversity of land birds in the Florida peninsula is abysmal relative to the rest of eastern North America.

The reduced numbers of species of some taxa in Florida has been explained at times by the so-called peninsula effect. For a variety of types of organisms, peninsulas often show reversed diversity gradients from base to tip, though the mechanism for this trend is difficult to pin down. One component for some organisms may have to do with the colonization and extinction dynamics of populations in the peninsula (I’m referring here to extinction of individual populations in an area, not an entire species). Because peninsulas have less direct connectivity with nearby land areas that may serve as a source of colonizing organisms, they may lack populations of species with poor vagility that are unable or unlikely to reach the more distant parts of the peninsula. Further, smaller extents of appropriate habitats in peninsulas may support smaller populations of the organisms that do manage to colonize, producing higher extinction rates for these populations. Finally, the range of habitat types may be reduced in peninsulas, preventing some species from colonizing in the first place. With respect to birds, the colonization argument just doesn’t work. Many of the bird species whose absence as breeding birds puzzles me migrate through or winter in the peninsula in large numbers, so getting here isn’t the problem. The population size and habitat availability arguments may contribute to Florida’s low breeding bird diversity, but they aren’t the whole story.

Northern parulas are abundant foliage-gleaners of hammock habitats, but other warblers and foliage-gleaners typical of forest habitats further north are absent.

For both islands and peninsulas, greater land area is related to greater species diversity, called the species-area effect. That may explain some of Florida’s lower breeding diversity, but not all of it. Look at the number of breeding bird species in the block that includes that little sliver of land called the Isthmus of Panama – it has around 600 breeding species! Land area isn’t everything.

One of the problems with the peninsular effect as an explanation for Florida’s low diversity of breeding birds is that this reversed diversity gradient of breeding birds isn’t restricted to the Florida peninsula – it is general to the southeastern United States. But even so, many bird species common as breeders in the southeast don’t make it into the peninsula. There’s something else going on here. One of the proposed explanations for reduced densities and diversity of breeding land birds in the southeast is related to the dynamics of primary productivity in temperate habitats. Simply put, temperate habitats further north experience a much more concentrated burst of plant growth in spring as all of the dormant vegetation begins leafing out around the same time, providing huge amounts of tender nutritious leaf material for herbivorous invertebrates. This burst of productivity works its way up the food web, resulting in a glut of food for the breeding birds. Spring certainly brings a burst of new growth in Florida, but probably not as dramatic and concentrated in time as in more northerly habitats. One factor contributing to this reversed diversity gradient among forest bird communities of eastern North America, which benefit hugely from this spring burst of productivity, is that more northerly bird communities show show both decreased extinction rates of individual species in the community, and lower turnover rates in community composition (number of species that disappear or appear between years). Stated another way, more southerly populations of these forest-breeding birds are more likely to disappear over time, and more likely to be replaced by other species.

Red-eyed vireos are far more abundant in migration than as breeders in peninsular Florida

The breeding bird communities of peninsular Florida’s broad-leaved forest habitats (hammocks) have always struck me as being particularly depauperate. Northern parulas are usually abundant, but other species of foliage-gleaning warblers are hard to find. There are no ground-foraging forest warblers breeding here at all, though ovenbirds are common in migration in these habitats. Red-eyed vireos, one of the most abundant breeding species of eastern deciduous forest, are present as breeders in many Florida hammocks, but at much lower densities than further north. It seems to me that both the productivity burst effect and area effects may be at work here. Many of the characteristic tree species of hammocks are evergreen; even though these species do put out new foliage in the spring in a leaf flush (live oaks, for example), the boom-bust nature of the resource experienced by birds breeding in forest habitats further north is not as dramatic here. In addition, hammocks themselves tend to be more patchily distributed and limited in area than do deciduous forest tracts in eastern North America. Smaller extents of habitat support smaller populations, which are more likely to go locally extinct, and exclude wide-ranging species that need large expanses of appropriate habitat in order to maintain viable populations. Hammock habitats in the peninsula are actually probably far more extensive now than they were historically; fire suppression in some formerly extensive habitats has resulted in expansion of fire-intolerant hammock habitats in many areas that once supported vast tracts of fire-dependent plant communities like sandhills and scrub.

Hammocks are historically patchily distributed habitats in peninsular Florida, but have expanded greatly due to fire suppression.

Other forest breeding guilds (a guild is a group of species that use similar resources in a comparable way) besides the foliage-gleaning warblers and vireos are equally perplexing. Tyrannid flycatchers, for example. Eastern deciduous forests further north typically support several species of forest-breeding flycatchers, including great crested flycatchers, eastern wood pewees, and Acadian flycatchers. We have lots of great cresteds, but Acadian flycatchers and pewees become harder and harder to find the further south you go in the peninsula. It’s tempting to suggest competition with insects as a possible link to the lowered diversity of breeding flycatchers in Florida – the superabundant and diverse dragonfly community must to some degree reduce the resource base, flying insects, on which tyrannids depend.

Do dragonflies, which presumably compete with flycatchers for aerial prey, reduce diversity and density of tyrannids in Florida?

Great crested flycatchers are common breeding birds in Florida, despite any competition from odonates.

Other forest tyrannids, like this Acadian flycatcher, are scarce as breeders.

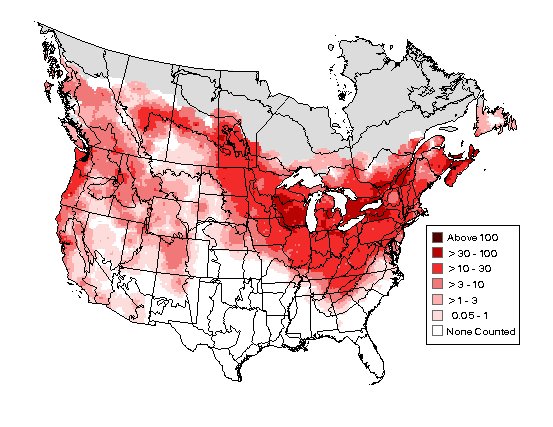

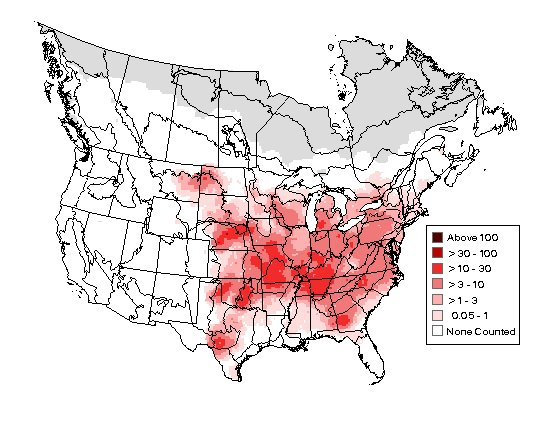

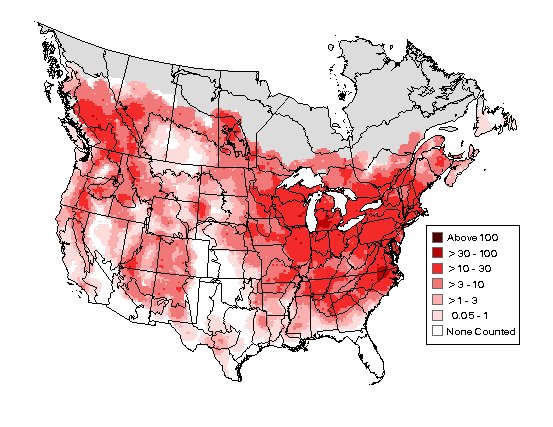

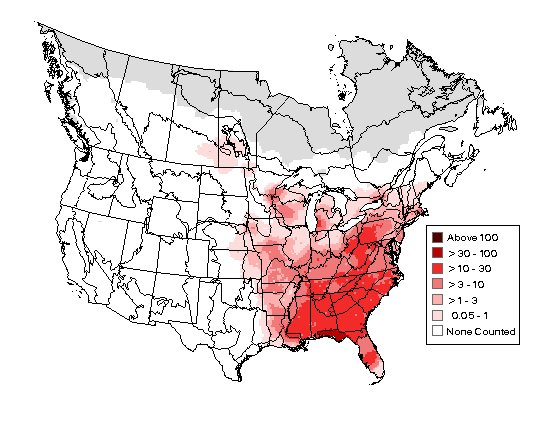

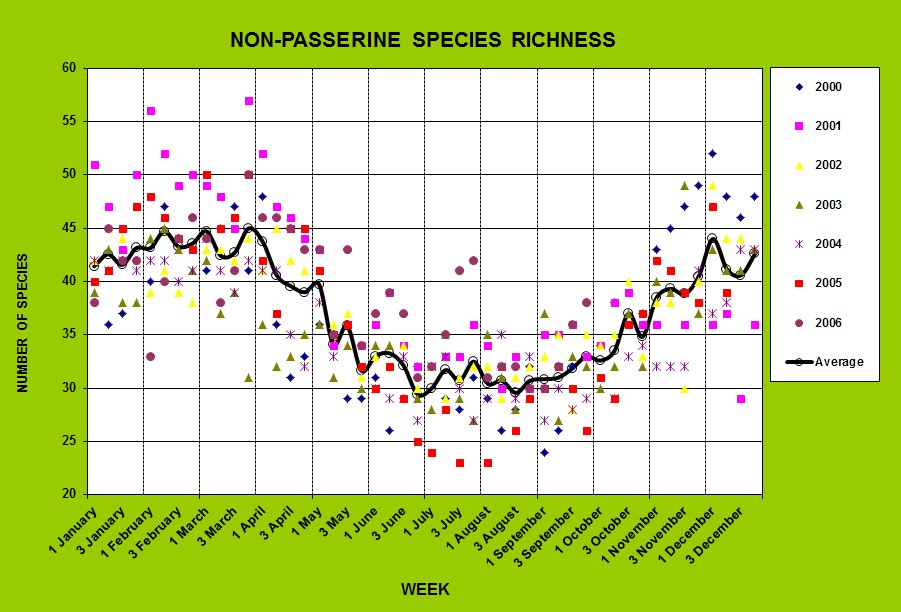

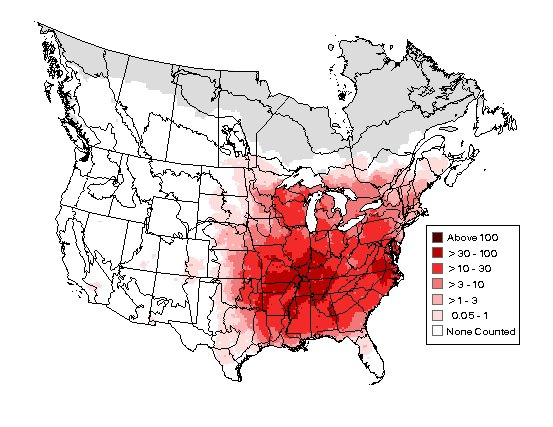

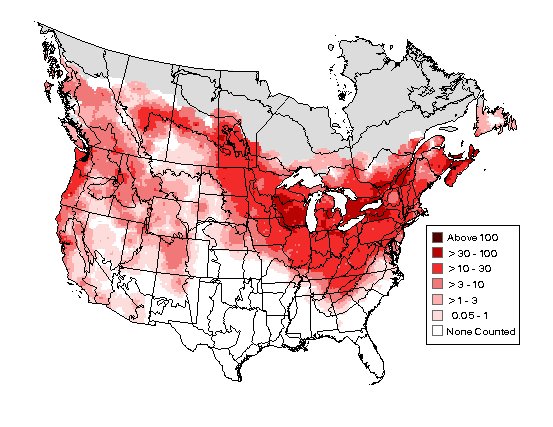

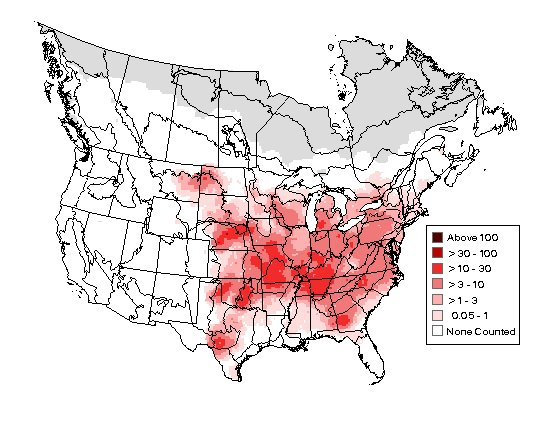

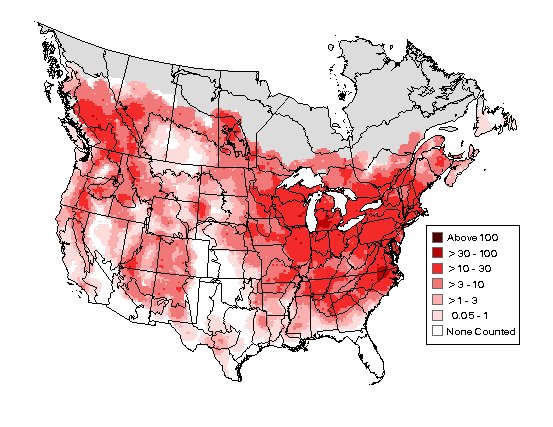

But none of those explanations seem to fit the sparrows. Most sparrow species in eastern North America are characteristic of disturbed or successional habitats – song, chipping, field, grasshopper, and so on. Successional or disturbed habitats by their nature are patchy in distribution, often limited in areal extent, and prone to disappearance over time as they are replaced during the process of secondary succession. Superficially, an old-field habitat in Florida is remarkably similar to one in Virginia, except that breeding bird diversity and density is dramatically lower. Examine the breeding density maps prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html) for any of the missing Florida breeders. I’ve pasted these breeding density maps below for four species: song sparrow, field sparrow, chipping sparrow, and eastern towhee. The low breeding abundance or complete absence in peninsular Florida of the three “typical” sparrows is apparent, and in marked contrast to that of the towhee, which actually shows increased breeding abundance in the central-southern portion of the Florida peninsula.

Song sparrow, a common winter resident that doesn’t breed in Florida

Song sparrow breeding abundance

Field sparrow

Field sparrow breeding density

Chipping sparrow

Chipping sparrow breeding density

Does the smaller burst of insect productivity in spring prevent species like this field sparrow from successfully raising young here?

Florida race of the eastern towhee, Pipilo erythropthalmus alleni.

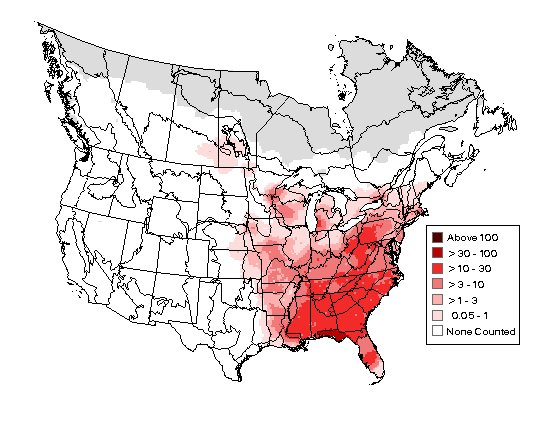

Breeding density of eastern towhees. Why are they so much more successful in the southeast than other sparrows?

So towhees love Florida, even though the productivity burst model may affect Florida towhees to some degree as well. Eastern towhees in Florida show the same shift in diet between winter and spring as do more northerly populations; they switch from a greater reliance on plant-based foods in the winter to more animal prey in the spring and summer. However, the magnitude of the shift is of a lesser magnitude in Florida towhees, who rely more on plant-based foods during the breeding season than do northern populations, perhaps hinting at a lower availability of insects in the Florida habitats used by towhees as well.

But what is it about towhees that makes them so successful in Florida, while all the other sparrows of similar habitats hightail it north in the spring? I’m still awaiting enlightenment.

Reference: Cook, R.E. 1969. Variation in Species Density of North American Birds. Systematic Biology 18 (1): 63-84.