August 4, 2014

Watching this Sceliphron mud dauber provision and seal off her sixth cell inspired me to document her building of Cell 7.

I’m one of those paganistic sorts whose main source of spiritual enrichment is my observation of and interaction with the natural world. Forget about talking snakes and burning bushes – I witness the miraculous every time I’m in the field. In the last day, I’ve watched a miracle unfolding without even leaving my house.

A couple of weeks ago a female black-and-yellow mud dauber, Sceliphron caementarium, began building a nest in the frame of my sliding glass door. To get there, she had to come into my glassed lanai while the glass panels were open. Once I noticed her building her first cell, I began leaving the glass room open as much as possible to allow her to continue her work. I think mud daubers are one of the first insects I learned to identify as a kid, before I had any real organized knowledge of nature. They are that common. Everyone knows them. I’ve always thought that the common Sceliphron in Florida, S. caementarium, is a particularly elegant looking wasp, and I knew the basics of their reproductive biology, but I’d never had the opportunity to watch one build at length.

Sceliphron caementarium, the black-and-yellow mud dauber.

For the next couple of weeks, my patio female added several more cells, and I frequently saw her flying in and out of the patio carrying mud balls. Yesterday, as she completed the sixth cell, I watched through binoculars from my living room couch as she provisioned the completed cell with a big green spider, and then a few minutes later capped it off with more mud. It was so amazing to watch I decided to set up on her and photograph her as she built, provisioned, and sealed her next cell. It took her between about 5:30 on Sunday evening and noon Monday to complete the task. It was a miracle.

The engineering and architectural feats of hymenopterans, the ants, bees, and wasps, are well known and all are worthy of marvel and awe. The fungus gardens of leafcutter ants, paper wasp and hornet nests, the hives of honeybees – all employ sophisticated design principles to achieve their ultimate goal, production and nurture of the next generation. But these are the works of colonial species, contributed to by dozens-millions of individual organisms. Solitary wasps like Sceliphron are perhaps even more awe-worthy simply because each female is on her own. She builds a stone castle for her children entirely by herself.

Larra bicolor, a deliberately introduced species of wasps that preys on mole crickets.

There is a huge diversity of solitary wasps, many of which share a common lifestyle – they build or dig some kind of nursery chamber in which to lay eggs, and then they provision the eggs with paralyzed insects of some sort that will be the larval food source. Cicada killers are one of the more obvious examples, but other provisioning wasps specialize on a variety of prey. Some specialize on caterpillars, others on crickets. Just a couple of weeks ago I found and photographed a beautiful crabronid (in the family Crabronidae) wasp that I had never seen before called Larra bicolor. This metallic black-and-red wasp was imported from South America in the 80’s and 90’s to control populations of non-native mole crickets. That’s how specific they are in provisioning their offspring – they hunt only mole crickets, which they temporarily paralyze with their sting. They lay an egg on the cricket, and when it recovers, it goes on its merry mole cricket way, now carrying a parasitoid wasp larva that will eat it from the inside out as it develops. Larra bicolor is so specialized in host choice that they attack non-native mole crickets almost exclusively; they ignore the native species of mole cricket, which as it turns out are attacked by a different, native species of Larra.

Liris wasp with paralyzed Gryllus cricket.

Last week, I saw another cricket specialist wasp in the genus Liris dragging a paralyzed cricket across the hammock floor at Beresford Park. Liris wasps attack only crickets in the genus Gryllus.

Leucage venusta, a common orb-weaver (Family Araneidae) in Florida. Sceliphron wasps prey on a number of orb-weavers.

Lovely Sceliphron is a spider specialist. They provision their nest chambers, or cells, with a mess of paralyzed spiders, which will feed the single larva that hatches in each cell. They exploit a variety of spider species, including both web-building and non-web spiders. But before they can do that, they have to build the chamber. They do this one cell at a time, which is provisioned, oviposited in, and sealed off before the next cell begins. That means that at numerous points some behavioral switch is engaged, and the female abruptly shifts her focus.

Bringing in mud for one of the lower courses.

First they must locate a suitable site; the one inside my patio was much lower than most I’ve seen, making it convenient for watching. Once a site is procured, the first switch is thrown, and they begin collecting mud. It seems to be a very consistent form and composition of mud, as the nests are incredibly uniform looking once completed. My female began building Cell 7 a little before 5:30 on Sunday evening, and completed it at about 7:45. During that time, she delivered and installed a new mud ball every 5 minutes or so. She was so regular during most of this time that I actually set my microwave timer for 4 minutes each time she left, and during that time futzed around the house, rushing back to the tripod-mounted camera when the alarm went off. Usually, she would reappear like clockwork within 15-30 seconds after I positioned myself. So to complete one cell she made somewhere between 25-30 mud-gathering trips.

Building the cell wall.

Shaping the clay.

Behavioral switch 2, from mud-gathering to building. The building process is remarkably delicate and precise. She deposits each mud ball on one side of the growing tube, and then manipulates it with her mandibles into a thin ribbon that adds to the length of the cell. The dexterity with which she accomplishes this task is impressive. It takes her less than a minute to form each mud deposit, and then she’s off for more. But interestingly enough, she never leaves immediately after finishing the latest course – she always entered the growing cell first, perhaps touching up the inside seams, and then emerged, usually to wander around the nest for a few seconds before launching into space to gather another mud ball.

She entered the cell after each course was finished before flying away.

Behavioral switch 3. She cycled between mud-collecting and building for the next couple of hours. The last I saw of her on Sunday evening was around 7:45. The females sleep away from the nest; my plan was to be back on the nest at first light so as not to miss the next stage, provisioning. I didn’t know what time that might be. I was an earlier riser than she. I first saw her around 8:15, and then apparently only for a final inspection of the now hardened cell. She spent a minute or so walking around her castle, and then took off.

The cell grows.

Grooming after completing the lip of the cell. She often groomed for a few seconds after finishing a course.

Inspecting the newly-hardened cell at 8:15 in the morning.

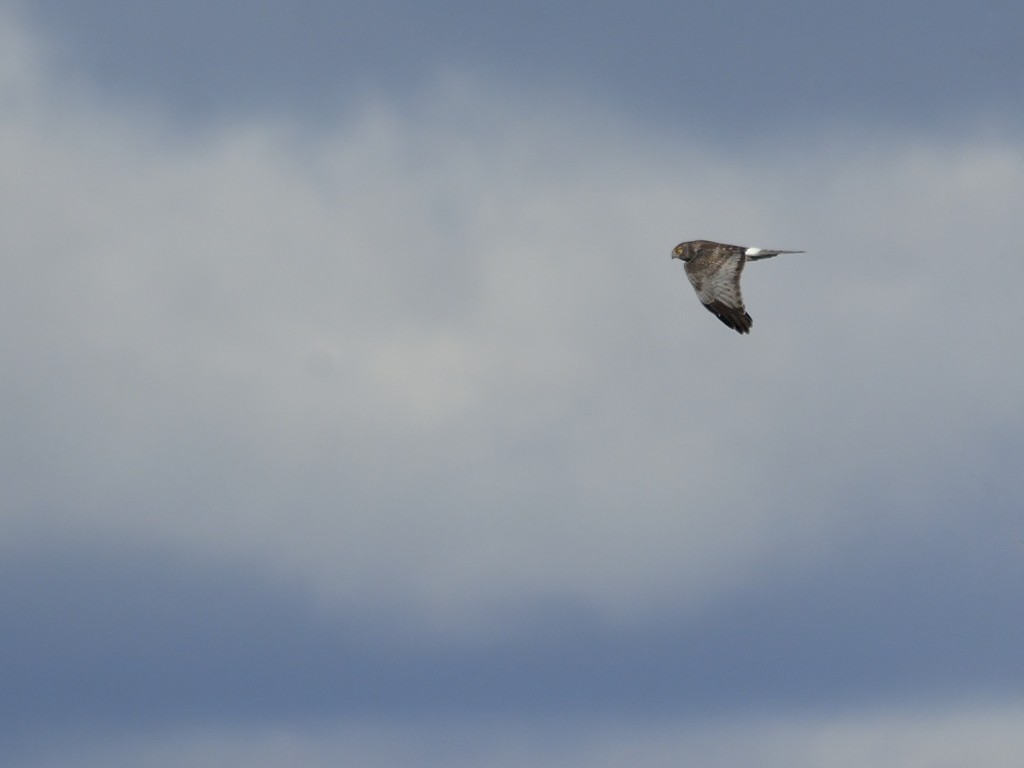

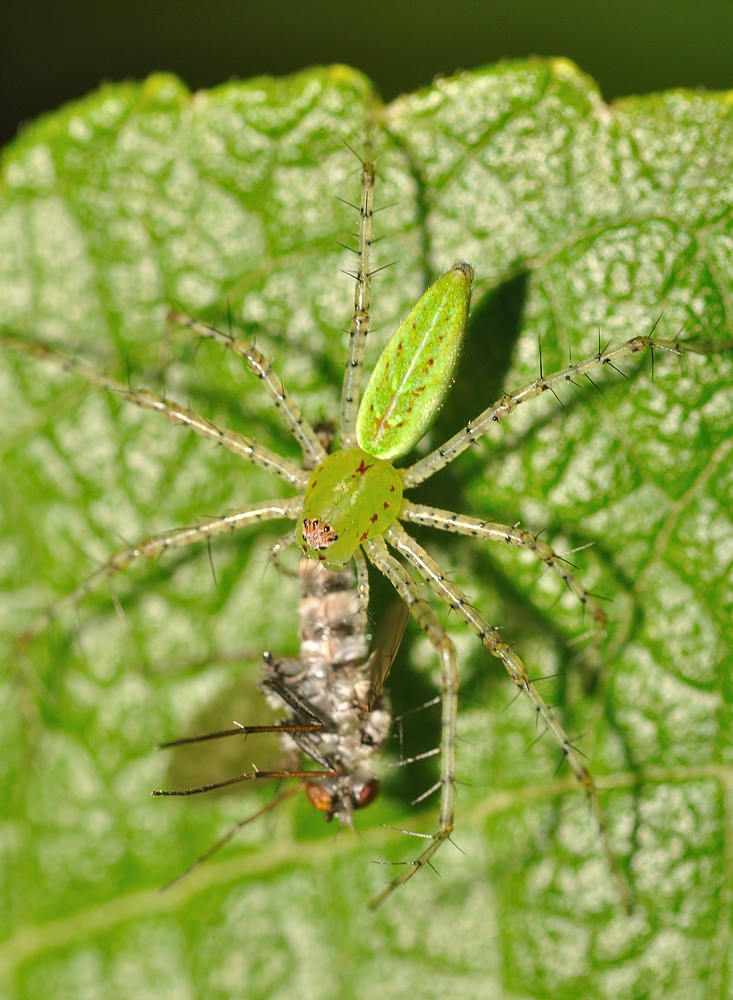

Behavioral switch 4. She was in hunting mode. Which apparently is not as regular and predictable as mud-gathering. I was hoping she would bring a spider in every five minutes or so, but it wasn’t until after 11 that I first saw her again. She was carrying a rather large green lynx spider, with its legs bent upwards over its back and almost parallel to each other. The wasp somehow did that, apparently, to make transport easier.

She delivers with a big juicy lynx spider.

Green lynx spider enjoying happier times.

Preparing for insertion.

Behavioral switch 5. Insertion. It took her a minute or so to position the spider and drag it backwards into the cell. Somehow she was able to get it in, legs last, position it inside and then exit herself from the hole. That was the only spider I saw her bring to that cell, though it’s possible I missed other deliveries because of her somewhat rude and inconveniencing loss of regularity. I did see her come back a couple of times and spend several minutes trying to tuck the ends of the protruding spider legs completely into the cell. So as far as I know, that larval wasp has only one spider to feed on, though in some cells there may be several spiders. In the Sceliphron species whose provisioning behaviors have been well-studied, the amount of food supplied for each cell is quite consistent, and based on total mass of the spiders delivered, not volume of the cell or number of individual spiders. So while the wasp is in provisioning mode, she is also keeping track, somehow, of the total weight of spiders she has delivered to that cell. Miraculous.

Come into my parlor, said the wasp to the spider.

Not as easy as it looks.

Dealing with those pesky legs.

She seemed somewhat befuddled about how to deal with the protruding legs. So she groomed.

Finally, behavioral switch 6. Capping. She seals off the cell by resuming the mud-gathering/buildingcycle. Watching her build the tube course by course was impressive, but seeing her turn that round ball of mud almost instantaneously into a cap of even thickness was even more so. She delivered five separate mud balls to complete the seal, thickening it with each new load, and in the last couple buttressing it to the surrounding cells. And then she looked upon her work and saw it was good. Seriously. After the last buttressing load, she spent what seemed like a longer period of time than usual wandering around her castle inspecting it. I actually thought while she was doing it that she had completed that cell. And she had. It was a bit after noon.

First mud ball forming the cap.

Smoothing the cap.

Off for more mud.

Mud load # 27.

Thickening the cap.

Buttressing the cell.

She began working on Cell 8 at about 1:30, and is still building the tube as I write this. Which involved another behavioral switch, returning to site-selection mode. I suspect the last inspection period was part of the decision-making process regarding where in the structure the next cell should go.

Sceliphron exhibits a remarkably sophisticated and precise chain of behaviors, most of which must be innate. Once she has completed all of her cells (which can range from less than 10 to over 40), she leaves her castle and offspring on their own. If her babies successfully navigate larvahood, they will emerge from their cells knowing exactly how to do everything their mother did. If they are females, that is. If they are males, on the other hand, all they have to know is how to hang around on the corner like a hoodlum and try to entice a female to accept a load of sperm. The disparity should be troubling and revolting to all decent folk.

Regardless of sex, though, nearly all of the operating instructions for these complex little beauties are encoded in the genes. Which is not to say that they are incapable of learning, and increasing their skill and dexterity with experience – learning must be involved in some aspects of their behavior. They must find a suitable nest site, and remember where it is and how to return to it from each collecting/provisioning trip. Still, a stunning amount of information must somehow be stored in the form of DNA, the primary function of which is to encode information allowing cells to build specific proteins. So, all of those complex and sophisticated behaviors are ultimately the result of the activities of specific proteins that constitute the major building blocks and functional components of all cells and tissues. And that is truly a miracle.