December 21, 2013

December 21, 2013

On Friday, December 13, a male painted bunting showed up at one of my feeders. Whatever vestiges of superstition I might harbor about that particular date should be forever banished by his appearance. It’s one of the luckiest days for me in recent memory. One of my most intense hopes for the winter bird season had been just this event. Others include big flocks of cedar waxwings swarming around the dahoon holly now fruiting in my yard, decent portraits of the sharp-shinned hawk that periodically strafes my feeders, the sharp-shinned hawk perched with a just-captured painted bunting grasped in his talons… well, maybe not the last one, though that would be a spectacular image.

I’ve lived in my current home for a little over 5 years, and in that time I’d guess I’ve seen painted buntings here 15-20 times. They aren’t uncommon birds when they’re in central Florida during their non-breeding season. But they are hard to see, particularly considering how spectacularly apparent (seemingly) the adult males are.

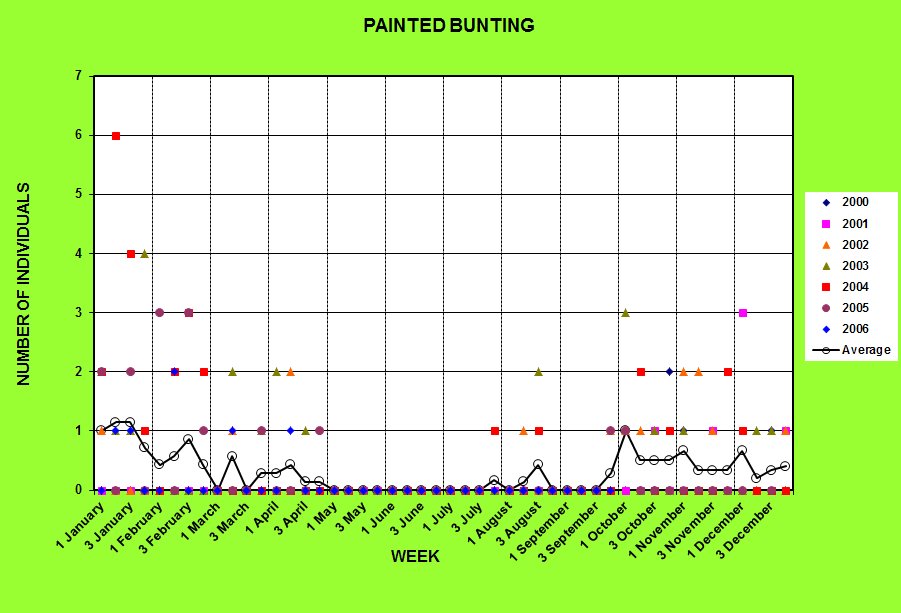

Seasonal occurrence and abundance of painted buntings at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area, Lake Co. FL

In the seven years I did weekly bird censuses at Emeralda Marsh Conservation Area in Lisbon, FL, I saw painted buntings regularly between late July and late April. During January, on a few occasions I saw 4-6 individuals in one day.

Of those maybe 20 sightings of painted buntings around my house, fewer than half have been adult males. More common are the “greenies”, the females and immature males that are uniformly citrusy green. Lovely birds in their own right, but they can’t hold a patch to the males. Of the fewer than 10 males I’ve seen, more than half were seen within the first year I lived here. The frequency with which I see both males and females has declined noticeably in the last few years.

The reason is simple – habitat. Big patches of habitat are better bird attractors than smaller patches. When I bought my house in 2008, the 50-odd acre tract directly behind it was natural habitat – mostly successional oldfield where a fernery used to be, but also including a small grove of several dozen orange trees. The oldfield habitat was in the woody invasion stage of succession, dominated by grasses and forbs, but in the process of being colonized by young hardwoods. I had lots of seral saplings like black cherry and persimmon scattered in little thickets and copses among the Andropogon-dominated grassland. Other ruderal taxa like Passiflora and Sida were abundant in spots. It was a bird magnet.

In my first winter here, I had grasshopper sparrows, a pair actually, a bird I had never associated with feeder visiting before; white-crowned sparrows, including a mature adult; vesper sparrows; song sparrows; and numerous indigo and painted buntings in or around my backyard gardens and feeders.

Then progress came. That 50-odd acre tract is now occupied by Citrus Grove Elementary School (aptly named, at least), and the amount of bird-attracting habitat has plummeted from over 50 acres down to my ¼ acre lot and its densely planted gardens. The diversity of birds passing through my yard, both as feeder visitors and transient migrants, has followed suit.

One of the first acceptable shots of the male I got. Rather have him off the feeder, but you take what you’re given, G.

So seeing a painted bunting these days, especially an adult male, is a miraculous gift to me. But once I had that gift, greedy bastard that I am, I wanted more. There’s a progression for the obsessed and deranged birder/photographer – see it well (always the best part), photograph it at even marginal quality if that’s all I can get, and finally, obtain high-quality images. Success at the first two stages doesn’t guarantee the last will follow – my experience with the buntings is that they can appear and disappear at any time.

The paradox of painted buntings is that though not uncommon, they are so infrequently seen, particularly away from feeders. I see them in the field perhaps 10 times a year, tops, including males and greenies. But watching them around the feeders reveals why – when they’re not actually feeding, they spend their time in the densest, darkest cover they can find, usually in the very center of shrubberies. They disappear. When they do venture into the open, they are quite flighty. They bolt quickly back to cover at the slightest movement or unexpected noise.

So their behavior is clearly related to the incredible gaudiness of their plumage – they don’t want to expose themselves unnecessarily to sharp-eyed predators, such as sharpies and Cooper’s hawks. Which raises a question – why don’t they molt out of this bright breeding plumage during the non-breeding season?

Other members of the genus Passerina, like the indigo bunting, do just that. The brilliant blue males molt most of their bright blue feathers after breeding, acquiring a female-like dull basic plumage. They then molt again prior to breeding in the following year, acquiring a new brilliant blue alternate plumage.

The extreme sexual dimorphism (or more accurately, dichromatism, or differences in coloration) between male and female buntings in the genus Passerina is suggestive of strong sexual selection by females during courtship and mate choice. Females apparently prefer more brightly colored males, which leads to evolution of more colorful males and increasing divergence between male and female plumage. Pigmentation in some male birds, especially the yellows, oranges and reds produced by the carotenoid pigments, is derived from feeding on plant materials; more brightly colored males may be more successful foragers. That’s a quality a female bird looking for some good genes for her offspring can get behind.

Dichromatism has costs for the males, though. They are far more conspicuous, and so in many dichromatic species, the males revert to a dully-colored, cryptic basic plumage once the breeding season ends. Male painted buntings don’t attain their brilliant definitive alternate plumage until they are nearly two years old, which also suggests there are negative consequences associated with the transition between a greenie and a spectacular adult. So why don’t painted bunting males revert to a cryptic greenie plumage after breeding?

That’s a puzzle for brains bigger than mine. My challenge right now is to watch these birds as much as possible when I get the chance. If I’m lucky, that will be all winter long for this particular male, but I’m not optimistic about that. He’s been around, visiting the feeders at least briefly every day, for 8 days. And today he came back with his little friend, Coco. She gonna’ be livin’ here too. (Big up to JJ for sharing the Coco clip with me).

Incredible images! And a heartbreaking story about your backyard habitat. So sorry, and Merry Christmas.

Pingback: A snipe hunt in Ocala National Forest | Volusia Naturalist