December 28, 2013

A number of common Florida birds are named for features that are rarely seen. Ring-necked ducks, ruby-crowned kinglets, and bristle-thighed curlews come to mind. This morning I was relaxing on the patio, savoring my best Christmas present, Joe Hutto’s endearing Illumination in the Flatwoods: A Season With the Wild Turkey. I watched and listened as numerous flocks ranging from a few to several dozen American robins flew over regularly; it seems that they are beginning to shift to their urban phase. While totally mellowing on this gorgeous gray Florida day, I was fortunate to not only see, but also photograph a feature of one of these common Florida birds that I’ve seen only a few times. Ever. The orange crown of an orange-crowned warbler. (If you’re still scratching your head about the bristle-thighed curlew reference above, give yourself a pat on the back; it’s a joke. I’ve never seen one, in Florida, Hawaii, or elsewhere.)

Many birds have plumage or structural features that serve as signals of some sort, and which can be widely variable in strength, or even their presence or absence. These graded signals allow nuance in communication between individuals. Exactly what is being communicated is often (usually?) hard to determine. Ruby-crowned kinglets have been tormenting me for years in my quest to photograph the full blown crest erection. Haven’t come close; a patch of red laid flat along the crown is the best I’ve been able to manage so far. I see ruby-crowns displaying their brilliant crest often enough that I have some intuition of its message – it seems to be an aggressive display towards conspecific males, and the degree of piloerection is an index of level of bad intent. Males will occasionally flare their crest in response to playback of ruby-crowned kinglet vocalization (though not while mobbing, suggesting it is a signal for conspecifics), and when interacting in chases and aggression with other males.

One of the more nondescript of Florida’s winter warblers, if it doesn’t show any prominent field marks like wing bars or head pattern, it could be an orange-crowned warbler.

In orange-crowned warblers, I’ve seen even a smidgen of the orange so few times that I have no idea when or how they deploy their display. A Google image search for orange-crowned warbler returns a ton of very nice images, but only a handful show any sign of the orange crown. And most of those are birds being held in the hand. My inference is that orange-crowned warblers never flare the crown to the degree sometimes seen in a highly agitated ruby-crowned kinglet, in which the red cap looks more like a mohawk than it does plumage.

Feather position alone can act as a graded display, with or without display of normally hidden color. The degree of elevation of the crest on a northern cardinal changes dramatically, occasionally disappearing entirely when an individual is alone and presumably totally mellowed out. For cardinals and blue jays, the erect crest is the default state. For many other “uncrested” birds, the flathead is the default state, and a prominent crest is displayed only briefly and infrequently. Think green heron here.

In other birds, the signal is always visible to some degree, but that degree varies tremendously. Male red-winged blackbirds sometimes throw me for a loop when I see them with their orange and yellow epaulets nearly totally concealed by other feathers. If I miss the sliver of yellow visible, I’ll begin to try and turn the bird into a more uncommon blackbird. At full display in a singing male, the epaulets are like brilliant orange-red flames.

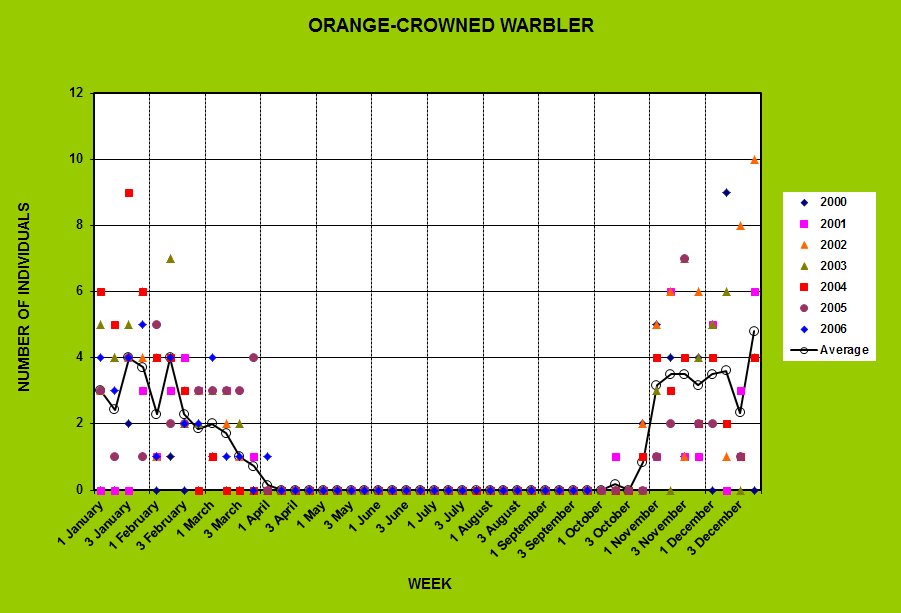

Though I almost never see their orange crown, I see orange-crowned warblers fairly often, usually as single birds traveling with mixed-species winter flocks that can include titmice, chickadees, yellow-rumped warblers, kinglets, gnatcatchers, and small numbers of a half-dozen or more small passerines. I love mixed-species flocks. Orange-crowneds are one of the latest of the wintering warblers to migrate into Florida; while doing my Emeralda bird surveys, they usually didn’t appear until the third week of October or the first of November. Between then and their departure in late March (late entry, early exit), I saw on average 2-4 birds per census. Rather slow, deliberate leaf-gleaners for the most part, in low- to mid-level vegetation. They seem to like to investigate clumps of dead leaves. I once photographed one at Merritt Island NWR feeding on a large inflorescence of the flowering vine Mikania scandens; it was feeding on insects attracted to the flowers as well as on floral nectar. Orange-crowned warblers will puncture the base of some long-tubed flowers to gain access to the nectar. Seems like a very tropical behavior to me, though many of these birds will remain in the mild but temperate southeast for the winter.

Through most of the winter in Florida, the orange-crowned warbler is a very reliable bird, though I never see them in large numbers. I once saw a small flock of 4 traveling together in my backyard; they were leaf-bathing on a drizzly February afternoon in the wet foliage near the top of a big Senna bicapsularis. I saw a hint or two of the orange crown on that day as well.

The bathing orange-crowned today was taking the more formal soak and fluff in the birdbath, and I was able to watch him (only males have the orange crown, which probably says something about its function) for a couple of minutes. The orange crown was frequently visible, though it was probably coincidental to the normal feather fluffing and puffing that bathing birds do. There were no other orange-crowned warblers, or birds of any other species that I was aware of, nearby that this little guy might have been signaling to. Perhaps the relatively low population density of orange-crowned warblers accounts for some of the rarity of the display, especially when compared with the somewhat similar appearing ruby-crowned kinglets, which are typically much more abundant than orange-crowneds, and which often occur in larger numbers in mixed-species flocks.

I have to think even a highly enraged orange-crowned warbler’s display is still pretty subdued. The species account at Cornell’s Birds of North America Online has this brief tidbit (from Arthur Cleveland Bent’s monumental multivolume set of life histories of North American birds) about the orange crown display: “Male threat or alarm display can involve elevation of head feathers to display (barely) the orange crown patch (Bent 1953).” As graded displays go, the orange-crowned warbler’s is quite modest. So why does it give me such a thrill to see it?

Pingback: Lekking in DeLeon Springs | Volusia Naturalist

Hello, I would like to inquiry about the stunning photo of the redwing blackbird (full display). Are you open to Artists using your photos as references for paintings? Thank you for your time. Kind regards, Corinne

Hi Corinne – feel free to use any of the photos as reference.